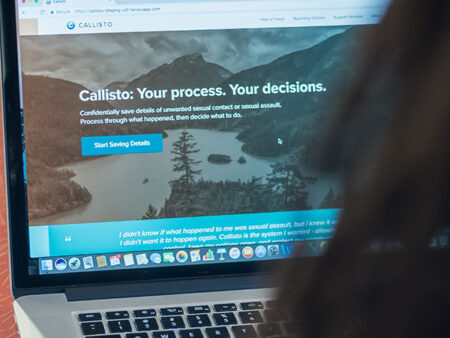

Callisto offers a variety of trauma-informed technological tools to empower survivors of sexual violence on college and university campuses. The tools are highly encrypted and secure and include matching survivors of the same perpetrator, recording memories of assaults using a trauma-informed incident log, and connecting survivors to a third-party Legal Options Counselor.

Tracy DeTomasi of Callisto spoke with Lissa Harris on July 19, 2023. Click here to read the full conversation with insights highlighted.

Lissa Harris: Can you please start off by introducing yourself and talking a little bit about the problem that you are addressing and how you’re responding to it?

Tracy DeTomasi: Thanks so much for doing this. At Callisto we really wanted to create a new solution to a problem that’s as old as time, and that is sexual assault, particularly on college campuses. And so 2,468,700 students are sexually assaulted each year on college campuses just in the US, which is a massive, massive number. And that’s one in four female students, one in five trans, non-binary, gender non-conforming students, and one in 15 male students. And these numbers really haven’t changed significantly over the years. I’ve been doing this work for over 20 years. It’s still kind of the same numbers that you hear all the time. And I think that when people hear a number like two and a half million, it really seems insurmountable, like, “What can we really do to do anything?” So I think a lot of people just do nothing or do what they’ve always done.

If we think about that two and a half million as not being the problem, but being a symptom of the problem, we can actually focus on the right problem. And the problem is the perpetrator. That’s what we haven’t really talked about in sexual assault for a long time, even as victim advocates. 90% of sexual assault on college campuses are committed by serial perpetrators who, on average, offend six times just while in college. If you can hold perpetrators accountable after two assaults versus six, you reduce sexual assault on college campuses by 59%, which is huge. That also means that the average size of the college campus in the United States is about 6,300 students. So if all of the math is correct, it’s about 125 perpetrators on the average size college campus, you go from two and a half million to 125, you can deal with 125 students. That seems much less insurmountable and much more doable.

At Callisto we have created a solution for this, to be able to start identifying those 125 perpetrators and, more importantly, helping the survivors of those perpetrators. We created a tool called Callisto Vault, and it’s highly encrypted. We use a lot of different cryptography to create this tool, which has two things in it. The main thing that it has in it is the matching system, so survivors can go in, they can create a free account with their .edu address, and they do three steps to enter into matching. First they put the state in which the assault occurred because the sexual assault laws are different in every state. And then they put the unique identifier of the perpetrator, so the perpetrator’s social media accounts, phone number, email address, because we can’t use a name because a name is not unique enough. And then they consent to be contacted by a legal options counselor.

Then, when somebody else puts in that same Instagram handle or that same TikTok handle, there’s a match. And it’s not like Tinder or Grindr or Hinge or anything where it’s not just like, “There’s a match.” What happens is we’re notified, but we do not have access to the perpetrator name or the survivor name. We’ve got a randomly generated case ID number because lists of perpetrators lead to defamation pieces and they’re not safe for survivors. We wanted to make sure that all of that’s encrypted where nobody can go in and hack the system to find this list. What happens is we’re notified, we can see the state in which the assault occurred, and we can see the school where the survivor attends, and then we assign that case to a legal options counselor.

This part of it might be changing a little bit just from the lessons we’re learning and as we’re scaling, but basically the survivor will meet with somebody confidentially and who can give them their options, whether it’s talking through what does a civil case look like, what does a criminal case look like, what are the processes for that, what is Title IX. A lot of people don’t know that Title IX exists or they don’t understand that Title IX can help if the perpetrator attends that school. Even something like, “I want to name my perpetrator on Instagram. What are the legal ramifications of that?” Whatever it is that they need. Then, if the survivors consent and want it, the legal options counselors work to connect those survivors, so then they can be personally connected. We know that this connection is really important for survivors because of the healing, the validation, the connection is just so powerful. They can choose what they do, whether that’s pursuing healing or justice, if that makes sense for them.

We also have what will be called the Incident Log. We’re changing the name of it in a month when we update it. It’s currently called the Encrypted Record Form. The Incident Log is really just a place for the survivor to document what happened to them in a really trauma-informed way to get those memories out. Trauma impacts memories and it’s hard to be chronological and know what details to want. So it walks the survivor through the what, where, when, who, who may have known, and what evidence you have, and helps them get that all out.

Nobody has access to that. We don’t have access to that. The only person who has access is the person with the password. It’s all stored really highly encrypted and then they can print that out and use it however they want, whether that’s taking it to the police, taking it to Title IX, taking it to a therapist, sharing with their friends and family, whatever it is that they want to use it for. Or they can just leave it in the vault forever. That is the solution that we have created for this huge problem.

Lissa Harris: You’re serving survivors directly, you’re engaging with them, you’re working with them, but are there other people that you’re serving and interacting with who are benefiting from your work? Are you working directly with college administrators? Are you working with other local nonprofits? Who are the other beneficiaries of the work that you do?

Tracy DeTomasi: We try to make partnerships with everybody because we know that survivors, particularly college students, aren’t thinking about this issue until it happens to them. So trying to get on a campus and talking to students about sexual assault, they’re worried about school, they’re worried about partying, they’re worried about friends, they’re worried about all the other stuff. So we work with a lot of different folks. Sometimes we work with the universities, whether that be Title IX, whether that be the residential components of the school, student life, whoever it is that really wants to help students and see this issue. We work with local nonprofits if they’re wanting to, that can provide support to the survivors, whether that’s a rape crisis center, a family justice center, or legal aid.

We work with different programs. We’ve got a great partnership with the Dance Network, which is a dance network where college students do dance competitions and they had some issues and they wanted a solution to be able to connect some of these serial perpetrators. We work with them to be able to provide education on sexual violence to their dancers. And so we are constantly looking for more partners for that work with students, particularly those in marginalized groups who, one, this issue impacts more. And two, they have less access to resources and the systems fail them more often and they don’t trust the system. Working with the groups that work with LGBTQ students, students of color, and students with disabilities, and seeing what work they’re already really doing with students to add in this piece of sexual violence. We also work with groups like Ed Rape On Campus, and It’s On Us, and Me Too International have been all really great partners because we can’t do this work in a silo. We want to be one piece. We want to stay in our lane of providing this technology as a solution to the people that are doing the hard work with survivors.

Lissa Harris: What makes your approach distinctive from other groups with similar missions or tackling the same problem?

Tracy DeTomasi: Really, there’s not really anybody else doing what we’re doing, and not in the way that we’re doing it as far as the technology goes. There are natural whisper networks and there’s Facebook groups, different things like that where you can name your perpetrator on social media. Those get shut down for defamation and people get sued. There was actually a case in the University of Arkansas a couple months ago where somebody created an Instagram post to call out the University of Arkansas’s quarterback, and then people started messaging them, and it grew really big. We looked at it and we’re like, “When is this going to get shut down?” And within two weeks, it was shut down and now there’s a million dollar lawsuit against the people who started it. So we really protect against false reports because we’re not a reporting tool and we’re not public. We keep it all very confidential so people can trust us.

Our technology, with how encrypted it is and how secure it is and how we’ve really thought about a lot of the risks around it, is very different. And again, this isn’t a solution that anybody has created before. There’s been a couple of groups that have tried or done it a little bit differently, but to really put the control in the hands of survivors and to connect them, with the sole purpose of connecting them, hasn’t been done. Typically journalists have done this. I mean, if you look at the cases of Harvey Weinstein, Larry Nassar, and Dr. Anderson, I think his name is. If you look at that, there were rumblings, everybody knew. And then a journalist was like, “I want to do a story on this.” And started investigating it and got the sources and there was one point person for the sources, but that’s not always safe.

It also requires a really talented journalist to do that, and it requires an outlet to think that that’s a good story. So what about the person who’s not the perpetrator, who’s not a doctor or not a famous coach or not a famous person in general or a rich person or anything like that, and it’s just your typical college student? Nobody cares about that story. So this is a really unique way to connect survivors that’s never been done.

Lissa Harris: I’m interested in the backgrounds of folks on your team. It sounds like you need a lot of high level expertise in tech and in the legal ramifications, and I imagine state by state legal issues. Not to get too into the weeds on this, but what kind tools are people bringing to the table on your team?

Tracy DeTomasi: We have a small but mighty team, and we’ve got a lot of volunteers that help us as well. I am a licensed clinical social worker. I’ve been doing gender-based violence work for over 20 years, and I actually started my career working with adolescent sex offenders as a therapist. I came from that offender side to really understand the dynamics of that. We have a lead engineer who also works with the cryptography board. We have some really high level experts in cryptography that assists him in developing the software and continually improving it because with any tech tool, it needs to be continually evolved and updated. We’ve got another social worker who does our social media to make sure that all of our messaging is super trauma informed, and we have somebody that has worked in higher ed for years who really understands student life and the unique challenges to student life in general.

And then we’ve got a couple of lawyers that work in this space that volunteer their time to educate because they see the power of Callisto, whether that is Title IX experts, people who’ve worked in criminal sexual assault for years, to get all of their feedback, as well as being those legal options counselors that have dedicated their careers to helping survivors both on the criminal and civil side of that. So yeah, I mean, it takes a lot of different people with a lot of different skills. The next skill that we’re really developing is marketing because our tool is only as effective as the amount of people who know about it. Making sure that people who have a .edu address know that they have access to the tool and know why it’s important. There are so many challenges with sexual assault that people just don’t understand why people wouldn’t report it, but less than 6% of people report to Title IX or police. So you’ve got 94% of people who have been assaulted who don’t do anything with it, and maybe they would if they weren’t the only one.

Lissa Harris: Is there an example or a story that you can share that illustrates the impact of the work that you do?

Tracy DeTomasi: That’s challenging because our system is so encrypted, we don’t talk with the survivors who’ve matched and we don’t have access to their information. However, I will tell you, when I go to conferences, when I go to different networking events or whatever, and I tell them what I do, this happens all the time. Somebody says, “Wow, that’s really great.” And then they pause, and I know exactly what’s coming next, and they say, “I wish I had this when I was in college. I wish I knew.” Because the two things that survivors always tell me are, “I thought I was alone for many years, and I always wondered if that person harmed somebody else. I reported because I didn’t want that person to harm somebody else. I felt guilty for not reporting because I worried about that person doing something else. I know that person did something to somebody else and we couldn’t hold them accountable.”

So I mean, just anecdotally, the amount of rooms that I’m in where survivors say that, and it’s not just women. I mean, obviously sexual assault impacts women and non-binary folks way more than men, but men don’t have an outlet. A lot of these coaches have been abusing men and boys for years, or there’s a lot of sexual abuse that’s happening in fraternity houses that’s labeled hazing and bullying. But really it’s sexual assault. A lot of times people are worried about false reporting, and I always say, “A man on a college campus is more likely statistically to be sexually assaulted than they are to be falsely accused. We’re talking about the wrong thing. Let’s look at them as victims as well.” So it’s hard to tell an exact story of Callisto from the survivor perspective of matches that have happened.

I think that you can see with the #MeToo Movement how powerful connecting survivors can be to elevate their voices. Survivors are talking. We’re always saying we need to give survivors a voice. I think we need to give other people an ear to listen, and they’re willing and they’re forced to listen when survivors band together and are louder. If we can get them connected, I mean, if you look at Larry Nassar, people reported him in 2001 and in 2002 and in 2004 and in 2007, to the police, to MSU, to USA Gymnastics, and yet he wasn’t held accountable until a journalist connected survivors and amplified their voice. And that’s what we’re doing.

Lissa Harris: If your software becomes more available on a campus, do you see the number of matches at that university increase over time? Are there metrics that you can use to see people taking up the tool on a wide level?

Tracy DeTomasi: With our pilot, we have about a 15% match rate. So that means that out of the entries that people put into the matching system, about 15% of them are finding other survivors of the same perpetrator. We have a match, and then a couple months later, there’s another person that adds to that match, and then a couple months later, there’s another person that has added to that match. We have ambassadors who are students who volunteer to spread the word on their campuses. And the campuses that we have more ambassadors at are the ones that we have more activity, whether accounts created or matches.

So we know that where students and student survivors trust the system through their friends, we have more success there. We’ve done fairly minimal marketing and outreach because we’ve really been focused on the tech. And with the pandemic, it was really challenging to connect with students in the last couple of years, but we know that when people are sharing it more on social media that we get more accounts, then we get more traction. People hear about it and then they wait, is what we’re finding. Nobody hears about it and then goes, “Yes, I’m going to do it right now,” because they’re debating, which is typical because it takes a survivor on average 11.2 months to report if they’re going to report. So it’s really hearing about it, trusting it, and then it’s a slow process. We want at least one person in every friend group to know about it so that if somebody in their friend group experiences sexual assault, they can tell them.

Lissa Harris: What do you think are some insights or teachable lessons that can be taken from your work that other people working in this space could use?

Tracy DeTomasi: I think listening to what survivors need and constantly realizing that sometimes that changes. When we first started, we were a tool for Title IX and we were assisting in getting more people to report to Title IX. We listened to survivors and we found out that they wanted an option before Title IX. The Title IX was not their solution, they didn’t trust it. They didn’t qualify for it, and they really wanted to know a solution before that. I also think that a lot of sexual assault people don’t report and that there’s an escalation in sexual assault. So there’s some sexual assault that is, we call it awful but lawful. It might not raise to the level of being a criminal sexual assault or you might not have a civil case, but it might’ve been really uncomfortable and really traumatic and still a violation, but maybe the next person, there was an actual criminal sexual assault, that together you can show the pattern.

Listening to survivors and understanding that pattern, looking at the offender rather than just the experiences of one or two victims, is how we’re going to really tackle this issue. Because if victims and survivors could have ended sexual assault, they would’ve done so years ago. We really need to focus on the behavior of the perpetrators and holding them accountable. And that’s about empowering survivors to be able to change the systems because the systems aren’t going to change until survivors have more power.

Lissa Harris: How do you measure success? What is the evidence that you’re making progress?

Tracy DeTomasi: That has been a challenge because we are so new. You can stay in a domestic violence shelter, you’re helping so many people and so many nights of stay or in a rape crisis center, you have so many calls or whatever and you get the feedback. Because we don’t have access to the identities of the survivors, that’s really challenging for us. But we know the power of connection, so a big part of success for us is the amount of matches we have and then the amount of people that know about us, because the amount of people that know about us, it’s going to eventually turn into matches. We’re still a very new tool that people don’t fully understand why they need it, how beneficial it is, will there be a match.

There’s a lot of questions, people still think that it takes forever to enter into matching, and it takes about five minutes depending on how long it takes you to find their social media accounts. So I definitely think that the match rate, how many people are using the incident log, and how many people are creating accounts on college campuses are some of the things that we’re looking for. We’re continually evaluating that because again, we are so new, we don’t even fully know what success is going to look like, which is terrifying and exciting all at the same time.

Lissa Harris: When did the tool roll out officially?

Tracy DeTomasi: Callisto Vault rolled out in the fall of ’21.

Lissa Harris: Very new.

Tracy DeTomasi: Yeah, very new. Right now, about 45 campuses have access all across the country. And in October we’re expanding to anybody with a .edu address. So while we’re geared towards students, professors, faculty, anybody with that .edu address can use it. We’re really looking at scaling and making sure that it can scale.Once all the .edus have access, we’re going to be able to detect those serial perpetrators who might have been accused in a Title IX complaint, and then they drop out of school and the Title IX complaint goes away and they go to a different school and then there’s another Title IX complaint, but those two schools don’t talk, or the police aren’t talking. We think that there’s a lot of connections but there aren’t the resources, sometimes the people in the systems are not great, but a lot of it is that the systems just don’t have the resources that they need. So having another resource to be able to connect this in a different way is going to be a huge success.

Lissa Harris: Are there other issues here? Like if iIt’s just a small fraction of students that are perpetrating these assaults, and presumably these are people who are aware of what they’re doing in a kind of sociopathic way, that as the awareness of how your tool works rolls out, that there will be countermeasures by people who want to get away with this and people switching their social media handles and acting to prevent the possibility of matching.

Tracy DeTomasi: Yeah, sure. And I will say that I think that there’s a spectrum of perpetrators. I think that there are very much the predators that are really evil and what we typically think of as the rapist, where they’re being very calculated about what they’re doing. And I think that there’s a lot of other perpetrators who are sucked into this negative misogynistic culture and don’t understand consent when you tell them, “Do you know how bad this is and how much that you’re hurting people?” And they really don’t, but just having one conversation is enough. So I think that this is going to get to the spectrum of that and how we hold perpetrators accountable can be a conversation with a fraternity brother, maybe that is all it takes, or it can be a police report where the person gets put in jail.

Is it going to catch every single perpetrator? It can’t because people will change their social media handles, but that’s going to be a very small percentage of people because, then, if you’re seeing somebody change your social media account all the time, why is that happening too? And so there’s some evidence there as well. We work well for the people who know the perpetrator, although that’s about 85% of people. We also think that when this gets to scale and more people know about it and use it, there’s going to be a deterrent, say at a party, and somebody’s like, “Don’t do that. You’re going to get Callisto’d.”

It’s going to make them think about their behaviors before they act and err on the side of caution. Right now, there’s the err on the side of, “I kind of want to have sex.” And so people push past boundaries. This tool will make them think about it a little bit more and say, “You know what? I’m going to err on the side of caution because I don’t want anybody to say that I’m a bad person.”

Lissa Harris: Every social innovator learns as much from things that don’t work as things that do work. Is there something that you tried that really didn’t work, that you learned something important from?

Tracy DeTomasi: I think the biggest thing is that we originally were working with Title IX offices and we were selling the tool to Title IX offices and it didn’t work. I think for a couple of reasons. One, Title IX offices don’t often have the resources, so they didn’t want to pay for it. They didn’t want to be on the cutting edge of something new. And a lot of Title IX offices don’t actually want to solve this problem because it’s going to cost the school a lot of money. I mean, if you look at the Larry Nassar case, Michigan State University just paid out $500 million from the lawsuit. So there’s a lot of schools that have covered up perpetrators, particularly ones that had power in their schools, and they know it and they don’t want to actually uncover it. And like I said before, survivors don’t trust Title IX a lot of times.

So that was something that we had to change, and it really changed a lot of our focus. We went from this “tech-for-good” nonprofit, and then we changed it to more of a social service nonprofit. We learned that we didn’t have to keep data to be extremely secure because Title IX offices had the data and they were the ones using it. We still want to be extremely secure, but there are drawbacks to that because now I don’t have connections to the survivors and I don’t have people who have connections who could talk to me about the survivors.

So we’re still learning lessons like that. We’re still learning lessons on how to scale, what the responses are, and there’s a lot of people that don’t want to solve this issue. They don’t want us to succeed, which is something that a lot of people who do want us to succeed don’t always understand. They’re like, “Who wouldn’t want this?” I’m like, “Well, a lot of people. That’s why we haven’t solved the issue of sexual assault in the past.”

Lissa Harris: How have you picked your 45 campuses? Is it places where people were less unfriendly to seeing this kind of solution implemented or bigger campuses?

Tracy DeTomasi: Some of them were legacy schools from our previous tool where they had to pay for access to Callisto Campus, which was the old tool name. A lot of it was we wanted to work with students, so we focused on where students asked us, where they reached out to us and said, “We need you, we want you.” There were a lot of schools on fire as far as this issue goes. The students wanted to do something and they pressured the school to do it. In some cases, there were administrations that reached out to us and said, “We really want access.” And so we kind of evaluated their capacity to spread the word about Callisto on their campus.

Some of the schools we don’t have a lot of contact with, some of the schools we have numerous students that are working to spread the word, and other schools we’re working with the administration. Every school’s very different and it depends on who you have in place that’s passionate about this to really work to make it spread and to be effective. But it really was about who wanted access for issues that they knew were going on campus.

Lissa Harris: Aside from funding, because that’s an issue for everyone, are there challenges that you faced, or that you’re still facing, that you really haven’t been able to solve yet? Whether that’s opposition in your communities or accessibility or other sorts of issues that you hit a stumbling block and you haven’t cracked it yet?

Tracy DeTomasi: Yeah, obviously funding. Funding, funding, funding. But beyond that, I would say that part of it for us is we are new. Because there’s nothing else out there like this, we don’t really know what our outcomes are going to be. We don’t know the impact that we’re going to have. Are we going to have a hundred matches or a thousand matches? We can do the math as far as the 90% and the six assaults and everything like that, but truly, we don’t know exactly what that’s going to be. And that’s a challenge for reporting numbers and what is a good number and what is not a good number, and collecting that data and still being secure and confidential, where somebody can’t use this list as a way to target the survivors who gave their name and trust us with the information. Part of i i’s the funding issue, but part of it is letting people know what our success is.

Not everybody understands that it’s success. It either seems too much, too little, it doesn’t make sense. And not everybody understands the power of connecting survivors. They’re like, “Well, now you connected them, now what? How many perpetrators are you holding accountable?” Well, we can’t determine that because it’s a five-year game, not a quarterly game. So a lot of our major data points and our major successes, what other people will perceive as successes, are five years out. It’s a long-term strategy and people don’t always want to wait or they don’t trust that this is going to be a thing. When you talk with survivors, it’s obvious how powerful making those connections are, particularly if it’s the same person that’s perpetrated both of them or all of them. We need to really get messaging out around that.

When I go into rooms, I can typically figure out within a couple of seconds where I need to start the conversation, depending on what questions people ask me. Do you have an idea of how pervasive the issue of sexual assault is on college campuses? Okay, yes, then I can go here and if not, then I’ve got to kind of back up. There’s a lot of people that are worried about false reporting and that’s their biggest concern, so then I’ve got to start there. And then there are survivors who get it. They understand why it’s secure, that there are defamation issues.

With cancer, everybody hates cancer. Nobody wants cancer. But people want to protect abusers. People want to protect perpetrators. They don’t trust survivors. And it’s not because they don’t trust survivors, it’s because they trust the perpetrator. You look at Brett Kavanaugh, people were saying, “We believe Dr. Ford. We just don’t think that he did it.” And that is the cognitive dissonance in this work. People are like, “Yeah, we believe the survivor, but we also believe the perpetrator. And if we know the perpetrator, we’re going to believe them more.” You need that power with the numbers. We shouldn’t need to connect everybody. It should only be able to take one. But because so much of sexual assault is behind closed doors and it is a, he said, she said, she said, he said, he said, he said, whatever the case may be, you need the, “We said.”

Lissa Harris: Can you talk about how you’re working to advance systems level change in your field? And you’ve talked about some of this already and how this is a long game, but beyond the individual cases, beyond the campus even, what’s the work on making some systems level shifts in this problem for you?

Tracy DeTomasi: When you start to connect survivors, the systems levels will change. You look at the watershed moment that was #MeToo, and I don’t know if people in the field really understand how big of a moment that was, but I have been working in gender-based violence for 15 plus years at that point, and it changed my work overnight. It was incredible. And the systems have changed because of that. Laws have changed, the statute of limitations has changed a lot, understanding how difficult the criminal justice system is and that you don’t actually get to put a pattern of behavior on somebody.

The more cases that we can connect and the more accountability that we can have, we can show more of the flaws in the system and we can show how very little this is being reported because the numbers are going to go up. We have to have the reporting numbers go up before we truly understand this issue. When you can connect survivors, the numbers will go up. Harvey Weinstein was not held accountable until there were how many women, Larry Nassar, Jeffrey Epstein, all of them were the same. And the system still hasn’t changed enough. While we’re not necessarily focused on the change of the system, we’re focusing on getting people together who will in turn change the system. And that is really important, but it’s a long game.

Lissa Harris: Obviously this is an issue in communities besides just college campuses. Do you have ambitions of making this a more broadly available tool for people to use in other kinds of communities?

Tracy DeTomasi: Absolutely. I had a call this morning with somebody from a religious community. We get contacted by entertainment industry, by unions, by maritime industry, by bartending industry all the time because sexual assault is not a college problem. Sexual assault is a society problem. And yes, funding, bandwidth, all of it, if someone just popped down a couple million dollars, I would be able to do all of this. But it’s about bandwidth and we are looking within the next three years, depending on funding, to figure out a way to give more access to different sectors. What we’re thinking about at this moment is really engaging in some of those unions and membership organizations that want to provide this as a resource to their members. Because a lot of people have said, “Well, you could get into workplaces.”

Workplaces, again, don’t want to identify this. NBC, CBS, wherever Matt Lauer was at, they knew about him. There were many people that knew about him and they didn’t want to address it because he brought in too much money and addressing it would’ve cost them millions just like it eventually did. Some workplaces are really great and they do want to deal with it. I don’t want to speak in full generalities, but there’s a lot that don’t. And so it’s the membership organizations creating the people because people have the opportunity to report to. HR people have the opportunity to report, but nothing’s happening with those reports and people don’t trust those reports. So having that third party external way to connect to people to understand what your options are before you go through that is just so invaluable. And so yes, eventually we will expand.

The great thing is that we’re starting with college campuses, but maybe that person goes on to offend when they get in the workforce, and that match will still happen regardless. In the bartending industry, you’ve got a client or a bartender, whoever is sexually harassing or assaulting people at a bar, and they also are at a college campus or somewhere else. So it will all connect because offenders are going to continue to offend until they’re stopped. I would love to just open it up, but for funding and resources and bandwidth and all of that, it’s not possible at the moment.

We’ve gotten international interests too. I talked to schools in England, we’ve talked to people who are connected to the French government, and Australia and all different places, and it’s exciting that people have so much interest. It’s just a matter of making sure that we go fast enough for the demand and slow enough, because this is so new, to make sure to identify and answer the questions that haven’t been asked yet about it.

Lissa Harris: What do you think is most needed from other actors or organizations you’re partnering with or universities to advance systems level change?

Tracy DeTomasi: I think with universities, it’s really understanding how the system and how the universities enable sexual assault to happen and sometimes even encourage it and hide it. A lot of times on college campuses they’re like, “Well, we don’t want this third party having the data.” In order to address it, they need to report to us, but there’s a reason that students and faculty are not reporting, so let’s have this outside resource to be able to connect them to then be able to be a collective voice and coordinate actions in order to report it. Understanding what their roles are and how embracing a neutral third party can be really beneficial for what they’re looking to do if they’re truly looking to end sexual violence. I mean, anytime you have a high profile case go through, the university always says, “We’re doing everything we can and ending sexual assault is a high priority.”

But what does that truly mean? Are you willing to make really difficult decisions of holding your star athlete accountable or your star coach or your star professor or your president or whoever the case may be? That’s when it gets more difficult and really understanding the role that systems and individuals and groups and culture play in holding up sexual violence is really important.

Lissa Harris: How do you see your work evolving over the next five years?

Tracy DeTomasi: That’s a big question. I think that in five years we’ll have a lot more data. We’ll have a lot more cases. We’ll really understand how survivors are benefiting because, again, we’re so new so we don’t know now. Hopefully in five years we have been widely adapted on college campuses as a resource. That we are a known name in communities and survivors know about us as well as getting into some of those other sectors. And within five years, having some potentially big cases where serial perpetrators are taken down and held criminally accountable and giving that voice and that healing to survivors. So identifying the next Larry Nassar could be a thing that we do. I’m confident that it will happen because survivors are looking for a voice. They’re looking to amplify their voices and they’re looking to find ways to connect and to find trusted resources.

Lissa Harris: I’m really curious about the software iteration, like how you decide to change things in the way that the software works and how that’s informed by survivors using it. Maybe you could speak just really briefly about that?

Tracy DeTomasi: I’m not a tech person, so I’m not going to be able to speak to the technical aspects of it, but we hear things. One of the things we heard was that we need some kind of data, we need to know who’s using the system and the demographics of the people using the system. So I talked with my lead engineer and I said, “How can we collect data while continuing the level of security that we have?” It took a little bit of time, but now we’re collecting demographics of the aggregate. We have no connection to any individual file or individual case of matching or the in inputted record form, but we can see who is using our system right now in the aggregate.

We’re also working on a way to connect with survivors who have matched, to be able to do a survey every six months, every year, to see what happened in the long-term. Did you end up deciding to connect with the person? Even if you decided not to immediately, did that change? Did that change after there were three matches, after there were four matches, after there were five survivors identified? We’re working on a really interesting way from a security perspective and a cryptographic perspective of being able to do that without collecting email addresses, which is very complicated. I throw these ideas out to my engineer and he’s like, “Well, we’re going to see if we can do that.” But it’s really about what does the survivor need, what are we hearing from survivors?

We get a new match and we’re like, “Oh, we didn’t really think about that. How can we add that into the system? How can we add the user experience to make that better?” Right now, we’re changing from the encrypted record form to an incident log because some of the stuff doesn’t flow as well from a trauma-informed perspective and asking the questions in a little bit different way. Sometimes it’s simple things like if examples were inside of a box and now once you start typing, those examples go away. So they’re not queuing you to think about all the other stuff that you can’t think of. So just taking those examples and putting them outside of the box instead of inside the box, simple little things like that.

Things that take into account how a survivor is going to think about this when they’re in a traumatized state, because they’re not fully processing when they’re in a traumatized state. So are they going to look and they’re going to click through? Are they going to read everything? If they’re not going to read everything, how do we break that up and make it into short sentences where they have to scroll through or click through in a different way than just having two big paragraphs where there’s a lot of important information that they need to know, but they’re not going to read it because they’re just going to skim over it because they just want to start. So it’s simple things like that. Our engineer is fantastic. He really thinks in a trauma-informed perspective. And there’s a lot of things where when we get to the design phase of adding new things in, he’ll say, “Well, what about if a survivor thinks about this?” And I’m like, “Oh, that’s a good thought.”

It’s continually challenging and asking questions and asking students and our ambassadors what they are hearing. One of the big things that we heard was people think that it takes a long time to get to do matching. So we started doing more demos to show that it takes three very easy steps. And then they’re like, “Oh, that’s it. I thought it was going to take an hour.”

Lissa Harris: Before we wrap up, I just wanted to ask about the name, Callisto, that’s from Greek mythology, right?

Tracy DeTomasi: It is. Our founder, Jess Ladd, took a class in college or something and heard about the Greek goddess of Callisto who was raped by Zeus, and was silenced and made into stars. I’m getting this very wrong, I’m sure. A lot of people ask about it because it’s not a name that people associate with sexual assault, but that’s also kind of powerful because people don’t want to talk about going to a rape crisis center. They’re not going to put a sticker that says, “Rape Crisis Center.” So having something that people can identify with their own story, with the story of this goddess who has lived on is really powerful. And when our founder heard that story in college as a survivor, she connected to it, and she was like, “This is my story.” And so we know that just sharing stories and sharing experiences can really just make all the differences from somebody else’s world.

Lissa Harris: Before we wrap up, is there anything that we didn’t talk about that you think is really important to add here?

Tracy DeTomasi: I want to emphasize that giving access to everybody in .edu accounts in October and making sure that people realize that access is free and we are a trusted resource and we are trauma-informed and we’re survivor focused, and that we need help spreading the word. We need people to know that this is something that’s important and we need people who work with college students, who are parents of college students, who are in college towns, to be aware of this resource because it is the power of one person suggesting this that can change the life and healing for a survivor because it’s really all about if a survivor tells their experience and they’re believed and they’re supported and they’re given resources, that change a lifetime worth of healing for them. Iit really can.

You asked about the five-year plan for Callisto. Well, the 20-year plan is that we don’t have to exist. I mean, would I love for us not to have to exist in five years? Absolutely. Do I think that’s realistic? No. But as a social worker, my job is to work myself out of a job. That’s the ultimate success. And honestly, in 20 years, hopefully this seems really outdated, and like why would we go through that step of connecting Callisto when we can just go to the police or we can just go to Title IX or we can just go to this other system that has existed, that we don’t need it. That would be amazing.

Lissa Harris: Well, I want to thank you so much for your time and for your insights.

Click here to read the full conversation with insights highlighted.

Lissa Harris is a freelance reporter and science writer (MIT ’08) based in the Catskills of upstate New York. She currently writes about climate, energy, and environment issues from a local perspective for the Albany Times Union, her own Substack newsletter, and various other digital and print publications.

* This interview has been edited and condensed.

Find other trauma-informed social innovations.