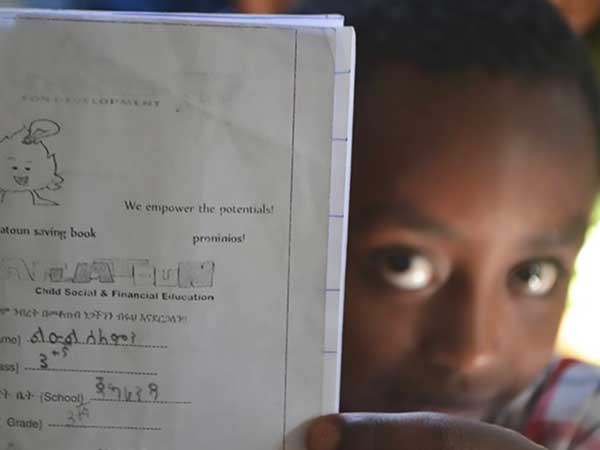

Aflatoun International offers social and financial education to children and young people around the world through a strong network of partners, in both civil society and government. They create high-quality curricula that are contextualized to local contexts or specific circumstances.

Roeland Monasch of Aflatoun International spoke with Lissa Harris on January 15, 2024. Click here to read the full interview with insights highlighted.

Lissa Harris: Can you start by introducing yourself, your organization and talk about the problem that you’re tackling and how you’re engaging with it?

Roeland Monasch: My name is Roeland Monasch. I’m the CEO of Aflatoun. I worked for over 20 years with the United Nations system and joined Aflatoun about nine years ago. The main reason I joined Aflatoun is because I really felt that in the traditional development response, it was very vertical looking at problems like health, education, child protection, environment. One of the key points I felt was missing was really empowering children and young people to address and prevent the challenges which normally the traditional development sector was addressing.

I also used to be the UNICEF [United Nations Children’s Fund] representative in Sierra Leone, and while everybody said I was doing a wonderful job in the health and education program, every day when I was driving in my Land Cruiser from my house to my office, on every corner of the street there were girls, 12, 14-year-olds, either pregnant or a baby on their back, selling peanuts to try to make ends meet. I felt that I was failing miserably, but there was no real response to these types of challenges. I mean, trying to get children into school, trying to get a protection program. But what do you give these girls who have already fallen between the cracks? How do you make sure that they can work on their own future and make sure that they can still make something from life?

I’ve been looking around, and what I noticed is that the one thing which really works is to provide these adolescents and younger children with some essential social and financial skills. As you know, nobody teaches children about finances even in the western world. In many nations, finance is a bit taboo. You learned it from your parents, but if your parents are living in poverty because they don’t understand money themselves, how can you expect that these kids are learning about it?

Basically, what we are saying in Aflatoun — and that’s why I joined, because it’s what I really passionately believe — is, of course, children need to go to school and they need to learn to read and write, but as soon as they can read, write, and count, you need to give them some basic skills about money because, like it or not, many of the children will never complete their education. They will not get a diploma. They will not get a job with the private sector or the corporate sector or the government. They have to start enterprising themselves. And if you don’t have the skills, you’ll be selling those peanuts on the streets… like every other corner of the street. So, what we’re basically saying is, make sure that you give these children some essential skills, and that’s what Aflatoun does.

Aflatoun is a social franchise. We develop content that is a combination of social and financial education. We take children through a five-step process: the first step is personal self-reflection. Who am I? What are my dreams? What do I want to do with my life? Sort of creating positive self-esteem. A lot of organizations do that, but it’s really giving them some hope and some passion for life.

Secondly, we embed them in their environment, in their community, so their role in the family, their role in the village. What can I expect from society? But what can the community expect from me? Sort of rights and responsibilities.

These are more like the social skills and, again, many organizations do these types of skills, but what we then say is, OK, if you want these children to actively act on this positive engagement, you need to talk about money if you like it or not. You need to teach them about savings or responsible spending — what are needs and what are wants — teach them about budgets, making a plan and, ultimately, learning by doing with their peers like developing small businesses and figuring out how it works in real life.

It’s sort of like a curriculum, but we’ve set up a social franchise, a movement, where we are not implementing ourselves, but we are sharing our content with local partners around the world. It’s in more than 100 countries and more than 350 partners. These are local NGOs, faith-based organizations, but also private companies, cooperatives, banks and increasingly governments, where we help them to locally contextualize our content for the specific setting.

It looks different in every country because it needs to be locally contextualized, and it needs to be owned by the people. So what we do is we train organizations. We train master trainers to contextualize, to use, and to integrate our content into existing programs. We have programs in southern Africa working on HIV/AIDS prevention for adolescent girls, where normally the program is only focusing on sexual and reproductive health. For example, in a place like Namibia, girls know much more about sexuality than most because they’ve been beaten with it every day. But they will still go to the sugar daddy if they don’t know another way to make money. So you need to also teach them about making a financial plan and how they can generate money, so that they can have a top-up for their phone, so that they can do their hair and buy the dress they want.

We also offer the program for children, juvenile justice, children who’ve been in contact with the law in some Asian countries. It’s child labor prevention programs, for example, BRAC in Bangladesh is using it for children who have dropped out of school and are being reintegrated into the main education system. They get the sort of catch-up schools by BRAC, where they’ve now integrated social and financial skills.

We have programs from Chile to China and from South Africa to Syria. It’s all over. It’s very localized. In every country it looks different because local partners really own it and make it their own product. And it’s also used as a very active learning methodology. It’s very playful. If you need to learn about money, you can’t just tell people how percentages work. They really need to start interacting with each other and learning by exploring. It’s a child-centered, active learning methodology where we empower teachers to interact with the children in a very different way. Instead of teaching the old-school remote learning, there are more facilitators where children are being able to ask critical questions, et cetera.

As they go through this program, they learn a lot of other 21st century skills, for example, democratic rights. I mean, they set up a club. They have to elect the chairman or chairwoman and then financial secretary. They learn to campaign, public speaking. They learn about voting. Through the program there’s a lot of others… We talk about responsible resource management. So it’s not only about money. It’s also about the climate, closing the tap, how you do it, recycling, et cetera.

Most people haven’t heard about Aflatoun, while we are actually quite a big organization. We’re in more than a hundred countries. And the reason why that is, is because we don’t provide anybody really with financial resources. We feel that you need to practice what you preach. You’re learning young people to be financially more resilient, then you should not be, as an NGO, holding your hand up to an organization in the Netherlands to fundraise.

Aside from not having a dependency between the [Global] North and the [Global] South, it is also a really empowering relationship, because we actually charge a small annual fee to these organizations.If you’re a small local NGO, you pay 250 euros a year. If you’re an international NGO, you pay 2,500 euros per country. The whole relationship changes because they’re not dependent or asking favors of us. By making a contribution, they become more customers and stakeholders for whom we deliver.

It’s a very empowering model; the people on the board of Aflatoun are elected representatives from over 350 these different organizations from different countries. Because they have to fundraise themselves, they have to generate money themselves, they talk about their own organizations when they engage with the international donor community or others not Aflatoun.

For example, Planet International in Egypt uses our content. If you go on their website, they call it Plans Adolescent Girls Empowerment Program. There’s no mention of Aflatoun on the website, but if you fly to Cairo and walk the slums of Cairo, they’re all singing Aflatoun songs. We’re the big unknown behind these programs, and that’s fine with us. We want people talking about their own organizations while advocating for social and financial skills for all children.

Lissa Harris: Do you work with governments as well? What sorts of organizations do you mainly serve?

Roeland Monasch: It is a very broad range. This could be a local faith-based mission NGO with two schools in rural Congo, but it is also the national umbrella organization of all the cooperatives in the Philippines — where we reach over a million children just through these, because there are 300 local cooperatives who have come together and they’re all using our content — and everything in between. It’s a very broad range. Most of our organizations reach about 5,000 children but, again, we also have an organization which reaches like 50 kids while some reach more than a million.

We have gone for a two-prong approach, realizing the strengths and the weaknesses of the different approaches. What we’re doing is we are really working with the local NGOs to focus on the most vulnerable children, which basically have already fallen between the cracks, who are not going to school anymore or are at risk, at a high risk of dropping out. And these are more smaller NGO programs. At the same time, we are saying every boy or girl should go through the program. So we’re also engaging with governments for a systems change approach where we are lobbying to integrate it into the national education systems.

We have also been lobbying the UN [United Nations] on trying to get social and financial skills through the Transforming Education Agenda, and we are seeing an uptake by more and more governments around the world. We are currently working with about 40 governments wanting to integrate it into the national curriculum. So a two-prong approach. On one side we work with the curricular departments, central banks, and the other side we work with local NGOs or international NGOs.

Lissa Harris: What would you say makes your approach distinctive from other people that are working in a similar space?

Roeland Monasch: A lot of people have been trying to set up a social franchise in recent years. Not everybody is successful. I think we are successful because we don’t claim visibility as Aflatoun as such, and we are not prescriptive. I think if you look at it, part of the secret sauce is the local contextualization, the local ownership. And then, what we also see is that the active learning methodology which we are using, empowering teachers… I mean, suddenly the eyes are open. It’s not only about the content on financial skills, but the research is showing that they’re also better teaching literacy and numeracy to kids, once they have noticed that they can engage with the children in a different way. So it’s the local contextualization of our unique content. It’s the active learning methodology. And then, I guess, the social franchise model are key elements of why it’s working.

Lissa Harris: Do you think that them having to pay you for the content makes them more able to push to make it their own and to do that kind of local contextualization? Does that help?

Roeland Monasch: Yeah, it does help. It is really that local ownership. And, yeah, it’s again, they have to own it. We sometimes come across that. To be honest, to join the movement, we’ve made it on purpose a little bit cumbersome. You always have organizations who just want to join and hope to get money because they’re with Aflatoun, and basically that’s all they want to join. We have them fill in a bit of a complicated form, so you see that they really are committed to becoming part of the network. It’s a sort of test case to a certain extent. And if you really just want to go and join Aflatoun because you hope there is money, you find too much work, in a way.

We are now over 350 organizations. It’s a breeding ground of innovations and sharing and what people really feel is that they’re part of something bigger. That’s the power of the network.

We are based in Amsterdam, but it’s developed in the Global South. It’s a platform where everybody can join, whether you’re a small faith-based organization or you are from a ministry of education, people all feel equally and are sharing.

Lissa Harris: Is there an example that you like that really illustrates the impact of the work that you do on the ground?

Roeland Monasch: What we are seeing is that our content is being integrated by the ministry of education in preschool. We call it early childhood education for sustainable development, but it’s really just teaching kids about delayed gratification. It’s how to interact with your peers, with your environment, learning to close the tap. But it’s really embedding some basic skills including financial skills with these children. And research is showing that it’s actually making an impact. They have done a small RCT [randomized control trials] there.

A good example is the Philippines, where it’s really at scale. We worked together with the Department of Education and the national cooperative umbrella body, where we came together to empower children with social and financial skills.

And we came up with a sort of win-win-win formula where the Ministry of Education was really interested in active learning methodologies for the teachers, where the cooperatives want to have young savers. We wanted to make sure that more and more children were reached with social and financial skills. We locally contextualized the content: translated it into a number of local languages, then, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education, trained all the local cooperatives to train the teachers in the schools and catchment areas how to teach social and financial skills. Basically, it’s a cascading model. It’s very powerful, and we are not paying a penny. They’re funding it themselves because the cooperatives see it as a cooperative social responsibility to invest in the future members of cooperative movements in these communities.

The ministry of education opens the schools for the local cooperatives. They teach the teachers, and the teachers embed these active learning methodologies in their classrooms. And lesson three of the five core elements of Aflatoun is savings, and the cooperatives then go in with local savings accounts for the kids and, therefore, they are able to benefit from it as well. Through that model, we have more than 500,000 children saving as we speak. There are more than a million kids going through the program as we speak, and they have more than 10 million euros saved by themselves at the moment in saving accounts. It’s all small, but it adds up, and it shows the power of creating a movement of small children who are all saving together.

At the moment, we are doing about eight randomized controlled trials. We have completed five randomized controlled trials in the past. And what we also see is that, for example, adolescent girls in western, eastern, and southern Africa are more likely to save, are saving larger amounts, and are more engaged in the classroom. So we have a number of indicators where we really see that this is changing their behavior.

We normally do an RCT before and after intervention with the control group. But we followed them four or five years later. Through mobile tracing, we were able to get quite a large sample of the young people who went through the program themselves. And what we could see is that those young people who went through the program are much more entrepreneurial, engaged, and have higher resources available compared to the kids who did not go through the program.

Lissa Harris: With the RCTs, do you work with universities on that? Is it like an in-house research project? How does that work?

Roeland Monasch: We initially started as an in-house. The first few were in-house because nobody knew Aflatoun and the subject was also not that interesting. But most of them are in partnership with universities. Some of them are from the North, but we try to work as much as possible with universities from the countries where we are working; I think that 80% of the RCTs are done within a local research institution.

Lissa Harris: And the countries where you’re working, are they all kind of Global South?

Roeland Monasch: The large majority is Global South and, to be honest, that’s for us the priority. But we also have programs in the Netherlands and, interestingly enough, in the more developed countries, there is a greater interest in the toddlers and in the parents. We also have developed a financial education program for new parents — basically vulnerable groups who are already in contact with social services — where we have developed a financial education program for parenting programs for vulnerable families. That’s being implemented also in Germany, Spain, Austria, et cetera. But the main focus is in the Global South. In sub-Saharan Africa, I think 40 countries out of the 53 countries where Aflatoun is being implemented.

Lissa Harris: What do you think the insights or the teachable lessons are that could be taken from your work that others could use and apply?

Roeland Monasch: We call it serious fun, but it is absolutely opening the eyes and empowering the teachers to interact with the young people, with children and young people, in a very different way. As I mentioned before, it is really empowering the educators, and that’s both the curriculum department, it’s the teacher training institutes, but then, ultimately, the teachers’ trainers and the teachers themselves engaging with the children in a different way, much more empowering, more facilitating them, so that these children are going on an exploration, on a journey. And it’s a crucial component of what we do.

For example, in Rwanda, teachers are also more likely to be more successful in teaching numeracy and literacy. The group who opened our doors to engage with the government there was the teacher trade unions. They were so enthusiastic, not so much about the financial education, but the way we were teaching children — how the lessons were organized in active learning methodology — that they wanted us to talk to their governments because they wanted our teaching methodologies to be introduced to all teachers in the country.

Lissa Harris: How do you measure success? What are the indicators that you look to see if you’re making progress?

Roeland Monasch: That’s an evolving area. We’ve done over a hundred studies, but the large majority — more than 80 — were just simple pre- and post-tests, because that was really to see to what extent the content is working locally.

So aside from measuring impact, this is also really measuring on, are the tools which we have locally contextualized being picked up by the children? The randomized control trials are focused on a number of indexes on self-confidence, positive self-esteem, engagement in the community, and entrepreneurial behaviors. Many of them are composites, but some of them are also pure and simple indicators which have been tested across the board. We feel quite confident now, but it has taken a while to measure the change. .

One of the things that has really helped us enormously is that ten years ago, there was much less published on financial education than there is today. Over the last five years — especially because of COVID — there’s much more focus on financial resilience in the academic world. Two years ago, there was a global review of 76 RCTs on financial education — adults, children, all age groups — that found a much more convincing impact than we have ever found before on the difference financial education makes on the lives of people. Not just only in knowledge but in behavior. That has helped us as well because even though it’s not our own research, it’s a much more broad evidence base for financial education.

There was also, separately and smaller, the review of 16 RCTs on the link between financial education, social education and sexual behavior and health outcomes in studies in eastern and southern Africa. There was also a strong indication that there was a positive association between combining social and financial skills and positive self-esteem, et cetera having a protective effect on health skills.

Lissa Harris: Sometimes in social innovation you learn as much from things that didn’t work as things that did. Is there an example of something that you tried that didn’t work out but that you learned something from?

Roeland Monasch: The biggest challenge we have and we will continue to have is quality assurance. We try to stay small and lean as Aflatoun, but we’re also growing a network. We don’t want to have an organization with offices in all these different countries. We would rather use our partners on the ground to engage with local authorities.

We’ve noticed that with some of our initial randomized control trials when we were still setting up the whole measurement system, we didn’t really concentrate on the intervention itself — how good it was implemented — and quickly noticed in the first two RCTs, we didn’t see that much results.

When we went back, we realized that actually the implementation was weak. It’s not so much that the content might not be working, but it’s the way you implement it. So we have a number of examples where we haven’t been building the capacity enough, or there has been a turnover among staff in these organizations where the spirit of the active learning methodology disappears and it becomes more like rogue learning again. With that, the quality of the intervention diminishes. So the biggest challenge is making sure that the programs are really being implemented with the vision we had in mind.

Lissa Harris: How do you work on that — especially since these are customers to you — how do you work on making sure that the quality of the programming you’re delivering is high enough?

Roeland Monasch: Two most important ways is because we are a network, there’s sort of a lot of peer review. We bring people together during the year on a regular basis, at least once by region and every second year at the global level, where people present to each other, share with each other. And because we are growing, we have more than one partner in most countries because we are not exclusive. In Uganda, we have 10 organizations which are using our content, and we try to bring them together as well. And they peer review each other. They support each other. That’s the first way, but recognizing that it needs to be really across the board systematically.

At the moment, we are in the final stages of rolling out a teacher certification program, as well as a master training certification program. In the beginning, we were very hesitant to do training online because we always felt that this active learning methodology was something you can only do through face-to-face trainings. So that was a bit of a struggle with us. But because of COVID, we were forced.

And it turns out that it actually works, even online. We have more and more evidence that even with research, again, that teachers which have been trained online are also actually doing a quality job. So we have been investing lately quite a bit in making sure that teachers are being trained, that they get a certificate, not only of participation, but they have to go through an online course with some tests, and then they have to come back after a certain period. At the moment, that’s three years, but we might even reduce two years, so that you refresh.

Lissa Harris: What are there broad challenges that you are still working to overcome that you haven’t been able to solve, like scalability or pushback or accessibility? What are the big challenges that you’re still wrestling with?

Roeland Monasch: The biggest challenge probably is the establishment in the education sector. So we talk about UNESCO [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization] and partly also UNICEF and the World Bank, the hardcore educationalists saying it’s about reading and writing. At the moment, there is a whole movement about transforming education that still is, most people do not recognize social skills. They do, but financial skills are not considered a priority at all.

To be honest, last year, or 2022 in September, the Secretary General of the UN called the Global Summit on Transforming Education because there is a real crisis in the education sector. And we lobbied for financial education, and UNESCO, we wrote them several letters. They didn’t want to talk to us. We asked for meetings. Very difficult. And ultimately — and that was also the power of the movement — we wrote letters to the DG [Director-General], UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank and the Secretary General’s office, and… It was signed by all these partners of the movement, so it was not only us in Amsterdam… but we organized within a week, and we [got] 150 signatures from all these organizations around the world that said, “This should be on the agenda.”

And interestingly enough, the Secretary General office said, “You have a point. Why don’t you come to New York?” We actually presented the concept at the Transforming Education Summit and the Secretary General included it in his vision statement. So, as a movement, we felt very successful. But once the summit was over, UNESCO just went on with their usual work, their own agendas. And you see this to a certain extent also with the World Bank and others. It’s not a priority for them, while we honestly still personally believe that it needs to be right high on top.

And, of course, people are talking about climate education and peace education, and they say financial education, go in the back of the line, but if you want… really for me, it’s nearly unethical what’s happening at the moment on climate education… We are now… everybody, the UNESCOs and the COP [Conference of the Parties]… we all need to go out there in the jungle of Brazil and Indonesia telling children not to chop forests, but if you don’t tell them how you, in other way, you can make money, it’s unfair.

And that’s what’s happening at the moment. Everybody’s jumping on the bandwagon… on climate education. No, it’s not climate education. It’s responsible resource management. It’s about how do you deal with your environment, the water resources, the nature, but also how do you manage money to behave in a different way? Unfortunately, it’s still so vertical that as financial education, social financial skills are still difficult to mainstream in the development agenda. That is probably the biggest challenge at the moment.

Lissa Harris: What do you think that pushback is about? Why is there so much resistance to seeing financial education, financial literacy as important?

Roeland Monasch: In most countries, talking about sexuality is much less of a taboo than talking about money with children, and that taboo still needs to be broken in many places. Curriculum departments of ministries of education are probably the most traditional government entities in most countries. What we have noticed is that one of the strongest allies for us are the central banks. There is also a movement after COVID on, not only on financial education, but on financial inclusion… really making sure that the disadvantaged groups, vulnerable populations in countries, are getting access to finance. And central banks are struggling on how do we make sure, and financial education has a role to play.

So when we knock on doors of ministries of education, they basically kick us out or send us to the back of the line behind climate education and psychosocial support, et cetera. But then all we do is we go to the central banks, and when we knock on their doors, they pull us in. They hug us and say, “Where have you been? Help us.”

Fortunately enough… that’s part of our model of being successful on national integration, in the political economy in these countries. Central banks are much more powerful than ministries of education, so they take us back to the ministry of education. They open the door for us. Then, of course, you have the critical questions about, how would it work? How do you have the evidence? And because we have local partners who are already implementing our content in all these countries, we actually have pilots on the ground as we speak… and then, when they see these local NGOs implementing it, they want to discuss how it could possibly be done at the national level. So the ally is the central bank, but the challenge is the establishment in the education sector.

Lissa Harris: Is it kind of a pipeline, like you start out with NGOs and faith-based organizations and smaller ones, and then you can show your results with them to the government partners that are at a bigger scale?

Roeland Monasch: In 95% of the countries, that’s the case. What we try to do is to work with a local partner and try to support them from behind to engage with the government, and in many places that works. But we also have governments who basically just want to work with an organization from the Netherlands because that sounds good. We have to be frank. Or they don’t want to. The NGO environment is not very supportive. So we also have countries where we really have to go ourselves because it wouldn’t work through the local NGO.

Lissa Harris: Can you talk a little more about how you’re working to advance systems level change? We’re in it. You’re talking about it, but just expand on that a little bit.

Roeland Monasch: Well, at the global level is the lobby and the advocacy and, as I mentioned, identifying the key stakeholders in the country beyond the ministry of education is very important. And that could be coalitions of local NGOs, but it is also the central banks, ministry of finance. And commercial banks, also the private sector, have an important role to play as well. You need to have them on board as well.

What we normally do is we take a process where, first of all, you need to convince them that it’s something to have a discussion about. Then, you bring all the stakeholders. And this process can take — if you’re lucky — two years, but normally it takes three, four years… and in some places it’s taken six years, but it’s a stakeholder meeting with all the actors around the table. Then you start mapping, OK, what’s already being done at the moment in the country on financial education. And once there is an agreement that something needs to be integrated into the education system, then you do a mapping of the existing curriculum on, is there already something there? What places are there where there needs to be decisions?

Some countries have a standalone financial education subject, but what we say is, try to integrate it in existing subjects. Then, it’s basically already funded. If you integrate it to maths and to social science or whatever subjects, the government’s going to pay for it itself, ultimately, because it’s part of that system.

So identifying the places where you want to integrate it, either standalone or through existing subjects, and lesson plan development. Then it’s training of the teacher institutes and then, ultimately, training of the teachers. And that is the biggest challenge because that’s expensive. I mean, the best example, at the moment, as we speak, is… Bangladesh would like to integrate financial education as a subject in a number of levels in the school system. But, if you want to roll it out, you need to orient all your teachers in the country for those age levels, and they want to do it at primary school level, and that basically [inaudible] every primary school teacher in the country. So we sat with them in a quick back of the envelope… basically [that] means that if you want to orient them for three or four days, just on the subject, it costs you about $50 million to do it, just for Bangladesh. Which is a small investment in the greater scale of things. It’ll have an enormous return on investment, but in the short term with financial education still being a sort of a novice idea, it’s very difficult to get that type of money, of course.

Lissa Harris: What do you think is most needed from other actors or partners to advance systems level change, whether that’s NGOs or philanthropy or governments, international bodies? What do other people need to do in order to make the systems level change happen?

Roeland Monasch: At the global level, and then ultimately spinning down to regional levels and national levels, it needs to have a sort of recognition of the role of life skills and financial education in education systems, and as part of that recognition, that it’s not an elective subject, but you really need to take all children through social and financial skills or whatever you call it. So it’s a recognition of the UNESCOs, international… For me, to be honest, my ultimately big goal is, we are now in 2024, but in the coming three, four years, we are going to develop the post-SDG [sustainable development goals] agenda for 2030, and we will have been successful if we have financial education as part of the new goals six years from now. That is ultimately what our big hairy goal is.

But, yeah, then the different stakeholders are the private sector, and specifically private banks, of course. And that could be corporate social responsibility, public financing, but also the expertise — bring people around the table. It’s a central bank who can advocate for the importance of financial education and linking financial education with financial inclusion, because, of course, there is a continuum there. Once you learn about finance and [there also needs] to also be in the finance systems, ways of accessing funds… where possible.

And then the local NGOs should, from our perspective, see where it can be integrated to address the challenges they’re dealing with, child marriage, to empower girls or teenage pregnancies or other developmental challenges for adolescents. And then donors have to also be part of that international dialogue, but also at country level, and start supporting these types of interventions. But, ultimately, if you like it or not, it needs to be a scalable approach. So what we see is that a few donors are now funding an NGO, which is great, but you need to be in mind on, at the same time, as a donor, to also think about national integration. The local NGOs need to continue to work on reaching the most vulnerable, but if you, you’re in the U.K. government or the USAID [United States Agency for International Development] or whatever, you need to also start thinking about, how do we integrate this into the core curriculum?

Lissa Harris: How do you see your work evolving over the next five years?

Roeland Monasch: It’s more and more engagement with governments on integrating it in national curricula. What we are seeing is that in more and more places, and sometimes, unfortunately, they want to have Aflatoun actively involved in the process and not only our local partners — although we work as much as possible with local partners — but they want to have somebody from us at the table there.

And then growing the movement. My vision is… At the moment, we’re 350, but by 2026, we want to have 600 partners, so really grow the movement. We want to be engaging — not having it integrated, but engaging — at least with 60 governments [about] integrating it into the international curriculum, to have that dialogue as much as possible and, hopefully, not be one of the few in the desert screaming for financial education, but having a much broader engagement with others… so where we can share our experience, but others actually can work with it.

And it is really my hope because we are seeing it. More and more organizations are starting to work on financial education but, very quickly, organizations are going to look at each other as competition, and we don’t want that. We want to have a platform where — what we are seeing at the moment, to be honest — we have a number of NGOs which have grown out of the Aflatoun network. They were small partners, but they have been successful and now they feel, “But I’m much bigger now than I was, like your other network partners. We want to have a special relationship,” or, “We don’t want to be part of it.” Anyway, try to remain… be a platform where we can bring people together. And it doesn’t have to be Aflatoun, but some kind of international platform where we can compare notes and share with each other.

Lissa Harris: We’ve covered a lot of territory. Is there anything that we didn’t get to that you thought was important to add?

Roeland Monasch: Yeah, to be honest, one point, because one of the things we are seeing is that there is an increasing interest in financial education, and we also do entrepreneurship education for the adolescents. They need it most immediately and rightfully, and we work with everyone on secondary education, but you can’t start early enough, and specifically because the most vulnerable kids are not completing their secondary education. They drop out during the first two years of secondary education or not transitioning. You can’t start early enough, so start during primary education already. It sounds odd, but at that place it works very effectively. And, of course, it’s different when you talk to a 16-year-old and you talk to an eight-year-old, but at that stage you can already embed these skills, which will be an investment for life. So start early.

Click here to read the full interview with insights highlighted.

Lissa Harris is a freelance reporter and science writer (MIT ’08) based in the Catskills of upstate New York. She currently writes about climate, energy, and environment issues from a local perspective for the Albany Times Union, her own Substack newsletter, and various other digital and print publications.

* This interview has been edited and condensed.

Learn more about organizations providing social innovations in financial education.