Landesa helps families in India gain legal control over their land. Supporting women to lead the digital land records documentation work has been a breakthrough strategy.

Pinaki Halder of Landesa spoke with Jessica Kantor on February 8, 2023. Click here to read the full conversation with insights highlighted.

Jessica Kantor: Could you start by introducing yourself and also describe the problem that you are addressing and how you are addressing it?

Pinaki Halder: My name is Pinaki Halder and I’ve worked with Landesa for the last 11 and a half years as the national director of programs in India.

The problem [we are working on] is persistent and pervasive across all the states in India, it is the problem of land recordation. The problem generally emanates from the fact that it is not clear to the community what a land record is or what significance land tenure security has. [There is also a lack of clarity about] the difference between documented records and updated records.

In the state of West Bengal [we have] partnered with the government, both the land reforms department and West Bengal state rural livelihood’s mission, which is an umbrella organization to mobilize hundreds of thousands of women to augment their skills for livelihood generation. But the common people, they do not have very good clarity [on land record issues].

The lack of knowledge and understanding about the land records is capitalized on by middlemen, people who charge very exorbitant fees to exploit this lack of awareness and knowledge about land records. When rural men and women [come to] the revenue office, the officers think that the issues are too complicated for them to understand. They pass on the message to a middleman, who [charges] an exorbitant fee to simply get updated land records. And there is a lot of harassment, time, and efforts for rural communities and people. Throughout India the situation is more or less the same. In some of the states, it is far worse than what we have seen in West Bengal.

In West Bengal an estimate shows that 2.4 million land records still are not updated. Without having updated records, and land records in the name of the actual owner even after the financial transaction is registered, people are unaware but are unable to access several government services without updated land records. They cannot approach financial institutions [because they need] this document as collateral to access loans or credit. And several government benefits, like the agricultural subsidy, [require] the person to prove, be it a woman or man, that the land is in her or in his name and the record is updated. [Otherwise] the application automatically gets rejected. This is the situation across the state and across several other states.

Jessica Kantor: What are you, and what is your organization doing to address this?

Pinaki Halder: Landesa has been in India for almost two decades. Initially we focused on efforts collaborating with the government to secure land rights. Several hundreds of thousands of communities had their land as homestead land actually and [we] started working in collaboration with the government to ensure that the landless community has land in their name through government distribution.

Starting in 2016, we found that awareness about updated land records, and accessing various government services without having proper or updated land records, is a major issue. In the meantime, the government of India requested Landesa to conduct a research study in three states, and what was revealed actually substantiated the reality that people don’t have land records in their name. People are in a very dire situation. They cannot approach government institutions to get their land records updated. And in the meantime, poor communities are exploited by middlemen [who tell them they have] to pay a large sum of money, which they do not have, and so they cannot get the records updated.

After these research studies were completed in three states, Landesa advocated [solutions] to the government. The government has all the records. Most of the land records are now digitized and available online. The platform is there. But this community is unable to handle that search engine [to find] the status of their land records and why it is not updated. But the opportunity was there.

So the government was more than convinced that they needed to do something. And Landesa is an ideal partner because [the government] is aware of Landesa over the last couple of decades. We promote land rights through inheritance, and secure land rights for the poor. So the government thought that Landesa could come up with an innovative approach. For the last five years we’ve had a women land literacy promotion program. We develop good quality trainers from the women self-help group, [they have] good intention, motivation and energy. The trainers subsequently reach out at the village level to promote land literacy, focusing on women’s land rights, secure land rights, and land records. [They provide clarity on] what documents are required for proving land ownership and where people have misconceptions.

Most of the people, 90% people in my experience of working with Landesa, have a wrong conceptual financial transactional deed registration, that means I’m the owner of the land. But it has to be a computerized record generated from the system. The government has created the opportunity to submit an application through this web-based mechanism, so we started working with a few women who wanted to do something beyond the knowledge acquired through land literacy sessions. They thought that they could serve their community if Landesa came forward and trained them. The government initially did not believe that women could be trained properly. [We had to] challenge the strong, patriarchal biases where women are not allowed to enter into the domain of land.

That initial barrier, the gender norms, was very strong and prevalent. But gradually, we started working with the women’s group and within five months we saw that the trained women could do an online application for getting the updated records. They [understood] what kind of information needs to be updated, how to search, what kind of attachments, documentations [need to be] uploaded. After hearing notices are generated, they follow up and get a copy of the digitized version of the land record. So this was the solution Landesa brought in. They started with two centers, then six centers. And now we have more than 100 centers across the state.

Jessica Kantor: Wow. That’s in five years of work?

Pinaki Halder: Yeah, four and a half precisely. Because during the COVID restriction, there was hardly any work. But still, we invited the Change Women to join us for online sessions so that they wouldn’t forget and could keep on practicing. And the online application submission process has continued.

Jessica Kantor: Is your work the first organization to try to do this in the community?

Pinaki Halder: Yes, no other organization has thought about it. Even the government never thought about it. Because picking up the thread of these responses coming from the community, when we conducted this research in three states, 84% respondents felt that women are the best proponents to be considered to offer this service. Because if it goes in the hands of the men it may generate more problems rather than solutions. So nobody else has ever tried this and it was really a kind of innovation.

Jessica Kantor: How are you measuring your success? Obviously, the more buildings that are working to make this happen, that’s one measurement. But what other evidence do you have that you’re making progress?

Pinaki Halder: We helped the government introduce a very simple monitoring [system]. Whenever a record is updated they charge a small fee, because another component for the women is entrepreneurship skill development. They charge a small fee for their own sustenance, for some income generation, and they enter all the details, your name, your family background, family names, et cetera. And then what kind of problem you are having, what kind of document you have, what kind of service you need. So all these things are recorded in a register and uploaded in an online MIS [monitoring system].

We have a very small team. But there are 22 districts and in 22 districts more than 101 centers, but the government [wants] moderate scaling. So our approach was to convince the government, [we must] capture enough data and information to claim [we have] good evidence for these women run land recordation centers. The government also agreed. There is a Google data collection instrument that is filled up at the end of every month from the centers, and automatically that hits the Google drive here at the state level, and we have access to that information. And during our field visits, we train women how to upload the information because, “The good work is done by you. And so please be careful that all these good works are actually recorded and you are getting your due recognition.”

Jessica Kantor: Can you share an example that illustrates the impact of your work?

Pinaki Halder: Let me start in this way because there was a strong patriarchal bias. We have seen several trained women leaders, they approached us that there is a rumor coming from the male group mentioning that these records generated by women are fake. So that was one challenge, but subsequently those have been addressed well by the women themselves. So that is the beginning. Sorry your question was, Jessica?

Jessica Kantor: Actually, you started answering another question that I have. So how about I ask you that question and then we can come back to this question. Every social change model has strengths and limitations. What are some of the limitations that you have seen in your work?

Pinaki Halder: As I have mentioned, the environment, the patriarchal society, the disbelief that needs to be dispelled. But the institutions, the local governments, came forward when they understood. The other challenge was that we did not get enough qualified women who were interested and received support from their family. Social mobility is another issue. There are several households where women are not allowed to spend four hours in a center, one kilometer from her house. And there is a thinking that she’s actually not doing justice to childcare responsibilities at home, not taking care of her in-laws well. These strong gender norms were a barrier and an environmental challenge. But gradually, once the people actually see and experience the land records coming from these women, [they] become preachers of the good work.

Another challenge is getting [enough] applications because there is an entrepreneurial component [to this response]. If a center has about 30 cases a month, that would help generate an income of two women managing the center, say about $25, $30. In Indian standards that is considered to be a good amount earned by women. So women can earn good money, but for that they need to have a good number of applications. The total applications pending is about 2.4 million and those 2.4 million people need to know what [land record] services are offered by these women at the centers.

Awareness generation is another challenge. It has been a norm that whenever any woman land literacy trainer or anybody from the board of directors is visiting any villages nearby, they carry small leaflets that [provide information about the center’s services]. “This is the name of our land rights center where you can come and get these five, six services. And you have to come here with these documents to receive the services. We are charging about two and a half dollars, $3 for this service. But in the market, they are charging $40, $70 even $100.” [Increasing awareness can help address] this barrier, they need to have a good number of applications for sustainability purposes.

The government is also thinking about putting banners at prominent locations where government services are offered. So that information is displayed through banners in important offices, the collector’s office, sub district collector’s office, local administrative offices.

Starting in 2023, [the main] question is capacity. You cannot [gain] community trust unless there is a strong belief prevalent in the community that women are really capable of offering these services online. There are several barriers in accessing the online service, the digital land reports, et cetera. So a capable center could be sustainable.

A big issue is earning the trust of the local community. Yes, women can do it. And if, say five applications are treated and five people get the updated land records, that helps in spreading [trust]. Say 500 community members will know immediately, “Oh this is only done only spending $3. And it was done within seven days, eight days.”

Another challenge, the last one, is building and developing an organic relationship with the local government and the revenue office, because the digital platform was created by the government. Anybody can access any digitized land record, but there are steps. The challenge is the community’s lack of knowledge about this, and also their lack of skill to handle this online platform. Once these women are able to successfully use this online platform, that eases and takes care of several challenges.

Jessica Kantor: My next question is about any mistakes you made early on or some type of failure that occurred early on in your work that you learned from. Can you share a story about that?

Pinaki Halder: In the beginning we did not think it was very important to bring the local government, the elected representatives, into this coordinated and collaborative approach. And there are 50% women elected representatives in India. Initially, we did not bother or did not care. But gradually, we have seen that women elected representatives are representing about 1000 community members, 200, 300 households, or maybe 500 households, and she is responsible for satisfying community needs. That was not in our initial thinking, but within a year or so we found the elected representatives are more knowledgeable so we insisted the land service provider and Sangha Institution, the board of directors, invite all the elected representatives in your institution, offer them a cup of tea and explain what [the center] can offer.

This mechanism was actually practiced by several Sangha women’s institutions and now we see the elected members, including women members, helping more service seekers approach the centers. This is working really nice, but initially we thought creating a good organic relationship with the revenue officials and local administration would be good enough. [We had not thought about] elected local sub government officials.

Jessica Kantor: That actually informs a little bit of the next question which is, are you and your organization working to advance system level change?

Pinaki Halder: Landesa definitely has a very strong focus on bringing about system changes. In general, we see the government has a complacent look at their own style of functioning. [They think] everything is fine, there is no issue. With our evidence and continuous presence in the field, we can show the reality to the government. By capturing good stories and sharing them with the government at the senior officer center, [we can offer] some ways we can jointly take it up.

In our research findings we found that local level institutions are not really bothered or not very careful about the community’s needs. We try to impress upon the [government] the community’s need of land records. We try to impress upon the government, can there be a village level court periodically, maybe once a month or once every two months, when a revenue officer from the government — because he’s the most trusted person, he’s treated like a god, “Oh he’s a revenue officer, he knows everything. Nobody else knows that much” — when a revenue officer [comes to] a community meeting organized by these women groups and explains, “See this is the difference between a land record and an updated land record. Why are you not able to access certain services?” Now there is a sincere effort by the government and has been taken over by the women here who are present. They’re offering services. “I’m here for the next three hours, please tell me what else you want to know.”

I am ensuring my faith upon these women. I have checked their ability to deliver the services. So that has helped strengthen the system. The revenue officers think that it is up to their will. Creating an opportunity in the mindset of the decision makers that the revenue system has to learn and understand the challenges the community is facing and [the need to] provide updated land records to them and offer the possible solution. This is something that has started happening.

Another system strengthening is that, Landesa has an opportunity to facilitate training sessions for this induction level training of the revenue officers. Normally Landesa is requested to take a session on women land rights and what are the new innovations. These young revenue officers who are joining at the entry level will get to understand what are the challenges and the barriers faced by the community and a solution the government has acknowledged. We can request that once they take over, after one month, that they just stand by the side of these women’s groups, the women’s institution, and help them acquire more knowledge. There will always be some complicated land records cases and when [the women] are seeking your appointment, could you please be a bit patient and explain to them that this is the particular case which is complicated and here is the solution. You can try to upload the application in this way. Now the young revenue officers can know about this new avenue for accessing the government based platform to update their records.

Jessica Kantor: Outside of the lack of understanding and the lack of training on the side of the revenue officers and the people who are in charge of them, what else do you think is needed from other people that are working in this area in order for there to be system level change?

Pinaki Halder: Landesa is currently providing the technical support. The main support is coming from the government. It is almost institutionalized. But there are a few areas that we suggest to the government for institutionalizing and sustaining this unique effort. There are a few things which the government may need to consider, such as how to support it and the promotion of land literacy, even among the men. Primarily the women are the target group, but even among the men, how it can be possible. And also supporting governments that have expressed their willingness.

Our willingness to support the government to educate the local civil government, the elected representatives, will be very [important] for sustaining these efforts because the local government is very strong here in rural India. Whatever they are preaching, they are promoting and are communicating to the community, so that cuts across. If they are coming forward and strongly express their intention, “Here is an option you can consider. And we can assure you’ll be treated well. It’ll be a homely environment. There will be a patient listener. You can talk about your problem. They will offer you the solutions. Then it’s up to you.” That is one continuous way this is happening, but there is a lot of further scope to actually strengthen these ideas.

Jessica Kantor: Do you have a specific example of the impact of your work, maybe a particular family or a particular woman that comes to mind?

Pinaki Halder: Women’s mobility outside the home is severely challenged within the Muslim community, so during a meeting organized by the administration, when several Sangha — I believe you are aware Sangha is a women’s cohort — several Sangha representatives were invited to check whether they’re in a position to consider opening up such a center. A couple of women from the Muslim community who were under the veil came forward after the session and asked us, myself and a female colleague who was there with me, they asked for a little bit of time to check whether they could do it. They’re Muslim women and they have studied only up to school level. There are some inherent challenges within their society. So I said, “What you can do, you can convene a community meeting at the village and we can be there to explain the purpose.”

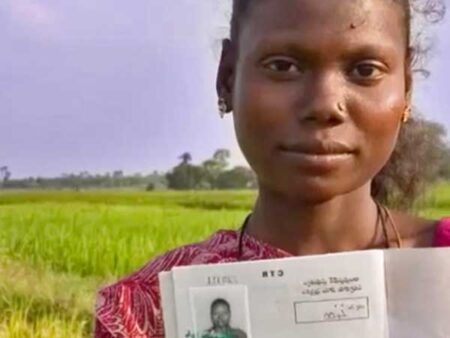

And Jessica, the maximum number of updated records that pass are within the Muslim community because of inheritance related complications. Sharia law has several complicated clauses. It was organized and we committed all our efforts and support to this women’s cohort in the village. It took a couple of months and then this lady, Arufa Begam, was speaking with us over her phone. I was checking, “Have you taken permission from your household people, particularly male members?”

[Arufa Begam said] “Oh yes, I have checked. And after you explained to the community, they feel if there is a center at the village level and women and men are welcome to visit, they will know about land records, know about secure land tenure, and know about the online web based platform services the government is offering. And my husband, who is also doing some kind of small business where he’s offering online identity cards, at a cost.” He also runs a computer, they have a laptop at their home, so her husband has given her permission to access the platform.

This particular center in Basanti, it is near the mangroves forest [and it’s] very inaccessible. [In the] Muslim population, women do not generally come out of their home. But these two women, courageous women, they’re offering the services and now it is one of the best centers running. One lady from Switzerland, a donor, came and she was amazed to see how these women have really come up with this. I think no one thought we could have this impact, this kind of change, overcoming the social barrier, overcoming the communication that can come through the women in a Muslim society. And now they’re offering land services.

Any woman is capable of explaining the land related documents because they were given thorough training to explain what are these columns and what does this information mean, how do you access this information, what do we upload, and how is the cash receipt generated online.

Last time I visited, a month ago, [I saw] one woman alone and also under the veil, she came with her husband. I asked her husband, “Why did you come here?” He said that his wife came for land literacy training and to know about land recordation services offered by trained women from this center. I’ve had a land dispute for the last 30 years, and cannot get any support from the government because of undated records. So now I have come, I shared my phone number with this gentleman [and said] once this is done, or if you are facing any challenge, please feel free to call me. After about 15 days he called me up, “I got the updated land record.” And he sent me a WhatsApp image of the computerized or digitized version of the updated land record.

Jessica Kantor: Where do you think your work is going to go in the next five years?

Pinaki Halder: We offer maybe 101 centers. That means 200 or 250 trained women. About 10% of them have become really proficient. They can handle issues. They can offer services in a very short period of time. But other women are facing challenges. Since the government cannot organize, they prefer the work to be done by Landesa, so we continue to provide handholding support by visiting these centers and [facilitating the] online sharing of screen methods that you can see. Also creating a WhatsApp group for knowledge sharing. If one woman shares a good successful disposal of a case, another 40 women in the WhatsApp group call are hearing it, or the Zoom call, they’re hearing it.

Down the line, in five years, I think some good efforts from the government is required to put more wages behind this innovative mechanism. The government has a lot of challenges in ensuring the records are updated. The government wants this, because to have a very good land market, the first condition the World Bank says is to have the records digitized and updated [to make them] easy for handling.

The government is very interested in seeing all pending applications for record applications disposed of successfully. But the government, at times, will find they’re clueless on how to do it. So in the government, now there is an excess between the revenue officers and the middlemen. They rely upon each other for reasons known to everybody. We expect the government in two or three years to take additional measures to promote these women run centers and strongly pass on the message and [sustain] the capacity of the women.

[Ensuring] enough applications are received and processed by these women to have some income augmentation that can help their voice and self-esteem within the household get stronger. That women are only child bearers and they do not understand land is a myth. The reality is women do understand land. Women are capable. Even the male persons, they’re not capable of providing online services.

Building an environment where the government trusts these women to provide services and develops their capacity. It has to be institutionalized. Over the next couple of years we will want to see the government develop a systemic approach for capacity development of willing women service providers.

Jessica Kantor: Is there anything else that the audience needs to know that we haven’t already covered, in order to understand your work, the impact of your work and where it’s headed? The limitations?

Pinaki Halder: This is only happening in the state of West Bengal. I think the central government, the government of India, has acknowledged and identified this as a national innovation. They were in a Zoom meeting, the honorable minister, secretary, she was their secretary where this one woman from a very remote village made a presentation [about] how they are successfully disposing of land record applications. So now the government is aware.

But we want to see the government take some good examples from here and promote it in other states. Because in a state like Bihar, in a state like UP, forget about land, women are never invited to come up in any discussion concerning development. These are the barriers and the challenges, the environment. I want to see the government getting more and more proactive. For this to happen, Landesa would love to engage at the central government level.

Land is a state issue unfortunately, so the government of India has restrictions, but they can always make suggestions. In that national rural livelihoods mission organized meeting all representatives from 29 states were there so they heard, they listened to the story. The woman mentioned that she was challenged by a few male middlemen when she was on her way coming back from the revenue office. The middlemen asked her, “Why are you visiting this revenue office every day? What do you have here?” But there were a few who received services [from her] and they immediately intervened and cautioned the middlemen, “Don’t get in their way. They’re doing a wonderful job. They are there to support.”

This woman explained before the national level audience and the minister. I look forward to more acceptance of this innovation. In the context, maybe it can change a little bit, but this can really address minimizing the land recordation related pendency. Hundreds of thousands of land reports are pending update. There is a website that indicated in August 2022 that almost 150 million land record cases [need to be updated]. The government needs to think more proactively and find alternate mechanisms, and this women’s institution is a good answer.

Jessica Kantor is an independent journalist specializing in health, human rights, and social impact. Her work can be found in Fast Company, Healthcare Quarterly, The Las Vegas Review-Journal, and others. She is a living kidney donor.

* This interview has been edited and condensed.

Find out what’s working in social innovation from other organizations working with women.