What’s Working

Insights About Climate Action

Connect after COP30

We were in Belém, Brazil, a few months ago—along with many of the innovators featured in our research. Don’t miss the chance to connect after COP30. (Want a recommendation of who to connect with? Drop us a line.)

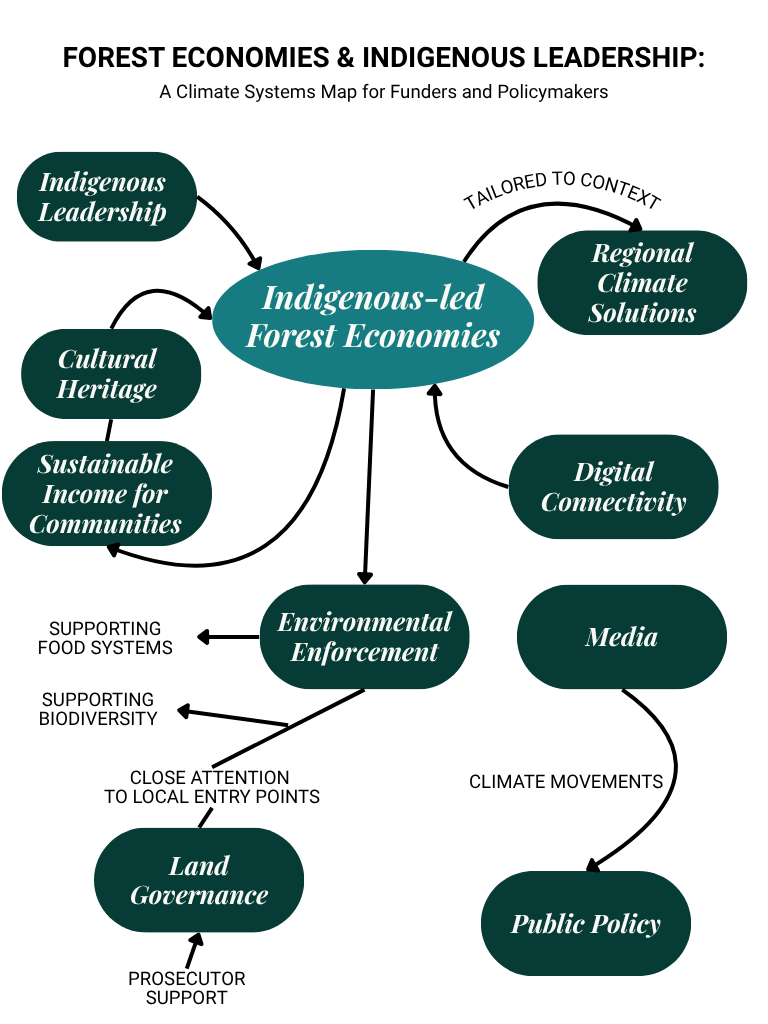

Indigenous communities play a critical role in advancing forest-based climate solutions. Our work highlights the interconnected pathways through which Indigenous leadership, regional climate strategies, land governance, and media influence shape effective and just environmental action. Forests are more than carbon sinks—they are dynamic bioeconomies rooted in cultural heritage and local knowledge systems. Understanding these linkages is essential for crafting interventions that are both impactful and equitable.

Jump to:

Cutting through the Noise:

What it takes to confront climate in an age of disinformation

We’re all culpable in the climate space. Whatever it is you feel guilty about, we all have it. We need to go beyond that and forgive ourselves. That stuff holds us back from being an effective agent of change.

With so much information overload on climate, many people are aware that something is wrong, but they don’t know which facts to trust or what steps to take. “The worst thing for communication is not silence, it is noise,” Maria Paula Fernandes of Uma Gota No Oceano said. “When there are too many conflicting voices, the audience loses their bearings.” Fossil-fuel giants spend billions to make sure the noise doesn’t fade. Calling out the hypocrisy in the 1970s anti-litter movement, Michael Khoo of Friends of the Earth argues, “We’ve built a whole culture of saying that you have to [recycle] in order to be a good citizen as opposed to stopping the fossil fuel, plastics, and petrochemical industries from dismantling the reusable glass bottle system, which they actively did step-by-step.”

Media agencies play a critical role in the climate action ecosystem to combat disinformation. Their strategic communications efforts, from organizations like mundo común, cut through the utopian and apocalyptic binaries to mobilize the public to care and to act. As one participant shared after attending mundo común’s workshop combining storytelling with somatic work, “I feel for the first time that I’m not separated.” That feeling of separation is one of the common challenges that media groups are working to address, as many people feel disconnected from both the environmental crisis and the solutions. Other organizations, like If Not Us Then Who (INUTW) and Uma Gota No Oceano, take varying approaches to bridging that gap: hosting retreats, such as mundo común‘s Cuerpo Enjambre (Body Swarm), where people are encouraged to leverage their own agency, or building trusted partnerships with media outlets to influence public policy.

The media is more than a messenger. It’s a catalyst for movement-building and to engage those who would rather look away.

Solutions:

Leverage partnerships to make strategic media interventions

The climate crisis doesn’t have the luxury of time to wait for journalists to find the stories that matter. Organizations must create opportunities to bring the story to the media. Research institutes like Imazon design projects with reporters in mind, building sites where media can easily access and amplify their work.

Other strategies consider timing in sessions with stakeholders; for example, Paul Redman of INUTW advises, “Our theory of change has been to show the right film to the right people at the right time.” The timing of Uma Gota’s media placement on “Bom Dia Brasil,” one of the biggest TV shows for politics and business news, helped clinch a policy win for its campaign. These gains take more than press releases; they require building what Uma Gota calls “a narrative arc.”

Finally, it’s equally important to focus on credibility and partner with organizations that people can trust. This could mean prioritizing artists and scientists.

Reframe grief and apathy into action

Going beyond traditional media channels like podcasts and Op-Eds, mundo común grounds participants in climate action through experiential, embodied storytelling, which includes weeklong guided immersions in the Amazon rainforest. After Enilda, an ecological activist, completed the retreat, she realized she could transform her land into a refugia—a place where ecosystems are restored after catastrophes. Stories like Enilda’s embody what Paul Redman calls “heroic narratives” that ignite positive chain reactions for change. In addition to these narratives, Redman also envisions a space for dialogue on forgiveness like a Climate Truth and Reconciliation Commission. “We can hear stories of how fossil fuels are impacting Indigenous communities, and the CEO who was there at the time can hear these stories and ask for forgiveness” Redman explained. “In that process, you create a vision for collective dreaming and collective work to solve the climate crisis.”

It’s not about telling people what to do; it’s about sharing resources so they are better able to respond to climate issues in their own communities. For example, INUTW offers a career development program with nearly 100 Indigenous creatives, whom they help to build networks, expand their capacity to engage NGOs and political movements, and garner support from the film industry.

‘Good Laws, Bad Implementation’:

The steep cost of being soft on climate

The problem is that you have good laws, but a bad implementation, and it’s a problem throughout Latin America.

As odd as it may sound, some land in Pará, Brazil, is owned by people who have passed away long ago. According to David Terceiro Nunes Pinheiro of the Ministério Público do Estado do Pará (MPPA), the ownership records in Brazil are so inaccurate that prosecutors routinely find property records belonging to the deceased, or in one strange case, more than a dozen land registrations in the name of a 16-year-old girl. These cover-ups make it more difficult for prosecutors to identify those responsible for threats against the environment. “They can just degrade and devastate everything, and the state will never know who is doing it,” Pinheiro said.

Corruption and lack of specialized staff also undermine the enforcement of environmental protection laws. Organizations like the Brazilian Association of Members of the Public Prosecutor’s Office for the Environment (ABRAMPA) say they have good relationships with NGOs that help with capacity. However, ABRAMPA is not funded by the government, so their work stops when their sponsorships end. Funders like Fundación Avina provide critical resources to ABRAMPA beyond money, such as publications and expertise, but more sustained investment is needed to support prosecutors as essential actors in addressing climate change.

These foundational governance issues must be resolved so that climate solutions can take root.

Solutions:

Governments can work with community and tech partners to improve accuracy of land registration systems

The current data in the Cadastro Ambiental Rural (the online land registration tool in Brazil) is not only outdated, but rife with flaws. “The people registered in the [Cadastro Ambiental Rural] are not the people causing the damage,” as Pinheiro points out, “Sometimes it’s a person who lives in another state, with no relationship to Pará.”

The government needs to work to close the timeline gaps between when land is registered and when the state confirms it. People seeking to exploit the land take advantage of those long timelines, and the state discovers the crime when it’s too late.

Currently, the government is partnering with Conexão Povos da Floresta for digital inclusion and forest-based community scholarships to encourage financial sustainability. But this partnership is only scratching the surface of possibilities. “The government should be the one doing what we’re doing,” Juliana Dib Rizende of Conexão Povos da Floresta said. “That’s why we want to be close to them, so they can learn how it can be done. We don’t have that much time.”

Toughen regulations while increasing incentives

As both Luciano Loubet of ABRAMPA and David Terceiro Nunes Pinheiro of MPPA note, it’s incredibly difficult to hold someone criminally liable in environmental law. But their chances of proving liability improve when they take the civil-law route. However, the financial penalties need to be more than a slap on the wrist to discourage the crime from happening again.

In addition to increasing penalties, another climate action strategy could be introducing incentives for protecting the environment. MPPA is developing a financial incentive to encourage businesses, especially agrobusinesses, to act sustainably. “The environment is a good way to make money and invest it back in the state,” Pinheiro observes.

On the prosecutors’ end, it’s vital to demonstrate the impact of the environment to increase buy-in from the investigators. When other stakeholders like environmentalists and scientists are brought in, the issues become clearer to prosecutors. In the Pantanal region, productivity increased by 300% after this strategy was used.

Beyond the “Carbon Sink”:

Harnessing the Amazon’s true economic potential

The forest holds enormous economic potential that, when approached responsibly, can sustain the livelihoods of the people who live there while benefiting the entire world.

On a small farm in the Amazon, one farmer had been following his family tradition of planting açaí. For four years, he planted trees, but on each attempt, he lost them all. He considered selling everything and moving to the city in search of a new job. That was until the Marajó Resiliente Project.

Marajó Resiliente is a collaboration among Belterra, Fundación Avina, Green Climate Fund (GCF), and Conexsus that equips 800 local beneficiaries with one to two hectares of land to launch their own agroforestry systems. “I have a small light,” the farmer said after participating in this initiative. “Maybe I can stay with my land and continue this life for my family, but in a new way.”

Despite successes like the açaí farmer, a widespread belief persists that farmers lack interest or capacity to act on climate issues. “From the government’s perspective, Indigenous people are an economic burden, not an economic asset,” as Gita Syahrani of the Koalisi Ekonomi Membumi (KEM) puts it. More than 1,500 farmers spoke out directly in the Farmer Voice Report from The CASH Coalition: Climate Action for Smallholders, highlighting their eagerness to get involved and stressing the importance of profitability.

Unlocking the forest’s full potential requires targeted investment in market access, local processing and equitable benefit-sharing systems, while ensuring renewable energy and land use efforts don’t displace traditional ecological practices.

Solutions:

Build infrastructure to support forest bioeconomies

A truly sustainable bioeconomy needs clear roles. Gita Syahrani of KEM puts it this way: “If you are offering a solution, you need to pinpoint from the get-go who is the doer and who is the payer.” Investments create the conditions for commodities to be viable in a competitive market. Within these considerations of what grows above the land, rights pertaining to ownership of what lays under the land – from minerals to water to other resources – should also be prioritized.

One of the economic tools for scaling that has been successful in the Papua province of Indonesia is KOBUMI, a trading company and logistics service created by EcoNusa Foundation and owned by 10 Indigenous community cooperatives. With a trading value of nearly $2 million, KOBUMI not only ensures quality control but also expands market access.

On the national scale, the Forest Trends Association achieved success in Peru, where its involvement in 50 out of 53 watersheds in partnerships across all the ministries (finance, agriculture, women, housing, environment and agriculture) has institutionalized ideas about water.

In India, Living Landscapes is currently conceptualizing a place-based stewardship model where a range of actors co-manage the ecosystem.

Shift the narrative on agroforestry

There needs to be a narrative shift around agroforestry, which is a sustainable farming approach that combines forestry and agriculture to not only maintain the land but also create more reliable livelihoods. Utilizing a dual business and philanthropy model to partner with the Quilombolas and Amazonian farmers, Belterra is currently leading that charge, and more organizations need to take notice. “It’s rare to see someone recognizing that this work is for climate resilience,” Thais Kasecker of Belterra said.

Heiner Baumann of CASH Coalition says farmers need more security (i.e., insurance) to mitigate the potential risks that agroforestry poses. Belterra, with support from Fundación Avina and GCF, has addressed this concern by implementing a results-based payment system where farmers are compensated as they move through different stages of the agroforestry process. Belterra currently allocates one-third of its budget to this model. Another strategy is to encourage farmers to experiment with a small piece of land. “Once farmers see and experience improved results from applying a practice on a small part of their land, or the land of one of their neighbors, they are much more likely to adopt the new practice,” Baumann said.

Groups like Kaleka, which has been working in Indonesia for many years, say funders should expect and even encourage organizations to fail upwards. For nearly a decade, Kaleka has been testing a market placement for nutmeg as a potential economic opportunity for farmers in the West Papua province.

Climate-Responsible Supply Chains:

How supply can sustainably meet the demand

There is poor faith between the buyers and sellers … How [do we] improve the faith so that [someone from the village] can sit at the negotiation table as an equal?

At the start of the millennium, while the literary fandom of Harry Potter was gaining momentum, a green revolution was just emerging. What began as a single Canadian edition on environmental paper grew into two dozen editions (including 12 million U.S. copies) and the creation of 40 new types of sustainable paper still in use today. “It pays to be shameless when you’re an environmental troublemaker,” Nicole Rycroft of Canopy, one of the organizations behind this movement, said.

Today, Canopy is partnering with a thousand brands across fashion and lifestyle sectors to move toward deforestation-free supply chains. Anchored by a three-pronged policy commitment that companies must agree to implement over a three-year period, these partnerships have been crucial to the success of Canopy’s work. The pillars within this policy include sourcing responsibly to avoid ancient and endangered forests, scaling next-gen solutions and advocating for change.

Collective action is the bedrock of responsible supply chains. Before a product reaches the market, brands, producers, and innovators must come together to make important decisions about how they will achieve their business goals and address environmental challenges. For climate goals to be achieved, there must be alignment between Indigenous stewardship of land and companies’ economic priorities.

Solutions:

Find common ground while partnering across the aisle

One of the effective strategies Canopy uses to confront tension is positive reinforcement. “Canopy is very consciously positioned as a carrot organization,” Rycroft said. “We’re a ‘pointy carrot’ organization, as sometimes we have to sharpen the end of our carrot and use it to poke, but our work is grounded in collective action.”

In another instance, the research institute Imazon partnered with timber companies long seen as opponents of conservation to help them transition from harmful to sustainable practices. With USAID funding, they piloted sustainable forest management on 500 acres, which the companies later scaled independently to nearly 20 million acres across the Amazon.

Mitigate power imbalances between buyers and sellers

Finding alignment among diverse stakeholders doesn’t make for particularly easy discussions, especially when distrust fuels power imbalances. In Living Landscapes’ work in India, the group noticed poor faith between buyers and sellers. As buyers, corporations often doubt that local communities are effectively managing their forests, while the sellers in the village communities feel these distant markets are untrustworthy. “If you’ve got authentic partnerships, then of course tensions are going to arise,” Rycroft said. “It’s more about the spirit and intent with which you lean into tension, because tension is often fertile ground for innovation and breakthrough moments.”

When building accountable supply chains, organizations need to confront these concerns over equity and create conditions in which Indigenous stewards’ autonomy can be fully recognized.

Localizing Efforts for Global Impact:

Scaling region-specific climate interventions

It’s about finding entry points in the moments that we have. … It’s a very opportunistic way of understanding the climate world.

In 2023, Brazilian recycling leader Aline Sousa and newly-elected President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva shared a stage. Sousa presented Lula with the presidential sash, catapulting sustainability into one of the biggest political spotlights of that year. This moment represents two entry points for climate action in Brazil: waste pickers and politics. NOSSAS utilizes both as mobilization tools for climate action. “Our idea is that if we don’t show Brazilian governments that the Brazilians stand up for the forest, we will fail,” Daniela Orofino of NOSSAS explains.

The climate crisis is a polycrisis in which each region faces its own unique combination of challenges and opportunities. This means what works in Brazil may not directly translate to success in India. Take waste management, for example: As Marcelo Mena of Global Methane Hub (GMH) explains, “[It] is capital-intensive in the global north and human-intensive in the global south.” In India, GMH identifies waste management and landfill fire mitigation as powerful entryways to reduce methane — an area receiving just 1% of climate funding despite its outsize impact.

Climate solutions work best when they are grounded in regional realities and designed around local entry points for impact. For the Asociación Ecosistemas Andinos (ECOAN), conservation of the Amazon and the Pacific regions began in Peru via its initiative, Acción Andina, which plants 3.5 million trees annually. Current laws in the Democratic Republic of Congo protect only above-ground resources, leaving what lies beneath unprotected. Yet mining is an entry point that remains contested among stakeholders. “I proposed to sit down and think critically and find ways how mining can contribute to conservation,” Dominique Bikaba of Strong Roots Congo shared. “They said I was crazy and asked why I thought it was possible.”

Funders who recognize and back these place-specific strategies can help unlock significant results.

Solutions:

Identify local entry points and fund them

We need to understand the systems, pain points and primary actors at the center of the issue. Some approaches to climate change are centered around taking down a singular, universal villain (insert: emissions, pollution). Marcelo Mena of GMH calls these methods “hammers looking for nails.” Funders need to widen their gaze beyond the traditional regions and charismatic species like tigers and butterflies.

Furthermore, when identifying entry points, consider them in conjunction with what can create the most local buy-in. For example, in India, Jagdeesh Puppala of Living Landscapes highlights the disconnect between research and action on the ground. Organizations might take cues from GMH, which uses waste fires as an entry point to discuss methane. In doing so, it is not only addressing climate, but also tapping into solutions for other crises (i.e., public health, income, etc.).

Expand geographic priorities

Currently, support is unevenly distributed across regions with tropical forests in Brazil, Indonesia and Congo getting particular attention. Living Landscapes operates in India, which includes the Western Ghats mountain region. Its Common Ground initiative supports local action in India, but it lacks the funding it needs to effectively collaborate with other climate organizations doing related work.

“If funders could broaden their thinking into other geographies, we would have more lessons to exchange with one another,” Jagdeesh Puppala of Living Landscapes said. “Most of the funders focus only on these areas, and many organizations are mushrooming in that.” As regions remain underfunded, localized solutions remain unexplored. Nevertheless, there should still be open channels of communication among regions to explore these possibilities.

Leaders on Their Own Terms:

Resetting the system for Indigenous leadership to thrive

When we talk about protecting the people who live in the Amazon rainforest, we are talking about protecting their cultures and their ancestral knowledge.

Indigenous communities are the proven protectors of the land. Yet in the current climate ecosystem, this acknowledgement functions as a pseudo-visibility: Indigenous voices are often centered in rhetoric, but sidelined in practice. “Other organizations working in this space will sometimes enter these regions with the best of intentions, but when their funding runs out, or maintaining long-term relationships becomes difficult, Indigenous communities are left time and time again wondering what happened,” ‘Aulani Wilhelm of Nia Tero said. “That repeated pattern of broken trust is hard to repair. This work requires a commitment to the long haul and a willingness to listen and understand why it’s often difficult to be trusted.”

Building genuine collaboration requires addressing mistrust on all sides. Building trust can lead to unexpected partnerships, laying the groundwork for Indigenous leaders to shine. Five years ago, Adinda Aksari of Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari (LTKL) could hardly believe the government would give space to youth in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, to become the leaders they are today, building new coalitions and institutions. This example shows how even historically adversarial relationships can evolve when trust is built and shared goals are identified. The success in Central Sulawesi was possible because LTKL took a back seat. “We have to understand that our job as the convener is complex, and we need to build practical pathways to give explanations to many types of stakeholders,” Ristika Putri Istanti of LTKL explained. “We have many different conversations with the government, the GSO, and the youth. We need to adjust our roles and identify the people we want to talk to. It’s not only about capacity; it’s also about capability and how to understand ourselves.”

The Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI) finds that language assistance can open opportunities for Indigenous leaders to access global visibility. Overcoming language barriers allows Indigenous leaders to engage as equal decision-makers in climate solutions. “As a coalition, we try to be very inclusive, but we fail all the time because we’re not inclusive enough sometimes to give a platform to someone who only speaks [their native language],” Madiha Waris Qureshi of RRI said. “We have to constantly challenge ourselves. It makes our job more difficult to translate our reports into multiple languages. It’s expensive, but it’s worth it.”

Solutions:

Embrace Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) as the standard governance model

Indigenous communities are essential to climate solutions, not only for their input but for their leadership in designing and driving those solutions. Each community is different. As Conexsus noted, effective engagement requires approaches tailored to local languages, norms, and systems of governance.

Acknowledge resilience with more investment in Indigenous-led systems

Begin by understanding existing knowledge and practices. In one village in Suriname, Minu Parahoe of the Amazon Conservation Team saw how four generations of traditional medical knowledge built community clinics, laying the groundwork for what could evolve into a formal national program.

Proven sustainability practices already exist. The coalition Koalisi Ekonomi Membumi (KEM) describes this wisdom as a form of technology, which it calls Lo-TEK, or Local and Indigenous Technology. Practices like the low-temperature distillation method are not new, as communities have been using them for centuries. “You can’t have a responsible bioeconomy unless your innovation and technology recognize what is being done upstream,” Gita Syahrani of KEM asserts. “The upstream level is the way the community manages its territory, and the way it processes.”

The Future of Climate Finance:

Funding solutions that address the polycrisis

Funding alone isn’t going to solve the problem, because you need a good mindset in place first for that funding to make a difference…We have to have the courage to do things differently and to do them quicker. Time is running out.

Indigenous peoples safeguard 80% of Earth’s remaining biodiversity – yet receive less than 1% of international climate funding. The funding needed to scale and amplify their impact is slow to arrive.

Some funders are working to close this gap. Nia Tero and Tenure Facility provide long-term, trust-based support that places resources directly in the hands of Indigenous communities. Rather than channeling funds through multiple layers of NGOs or partner organizations, they act as the intermediaries themselves, linking communities not only to funding but also to additional donors to build broader financial networks. “Funders are not very familiar with the systems change initiatives,” Jagdeesh Puppala of Living Landscapes said. “They feel that it is all hot air. How do we improve the confidence amongst funders on the need for system-level entrepreneurship alongside organizational entrepreneurship?”

In the agricultural sector, The CASH Coalition: Climate Action for Smallholders unites 13 farming-focused social enterprises to support smallholder farmers, a group that includes nearly 500 million families worldwide who are largely excluded from carbon finance systems. With a collective reach of more than 16 million farmers, the coalition helps them engage in scalable carbon mitigation work.

Climate Breakthrough adds another layer to this funding landscape by offering individual awards aimed at systems-level change, with the belief that this can also produce meaningful, localized results. “We need more space to fund work that doesn’t fit neatly into existing categories — projects that cross boundaries, sit between silos, or span multiple issue areas,” Michaela Koke of Climate Breakthrough said. “That’s especially true in climate, where the solutions we need next are interdisciplinary.”

In Indonesia, Kaleka has shown that when funders provide flexibility and allow timelines to stretch over years, sustainability programs can scale district-wide. Its experience underscores that lasting change often depends on patience and the space to achieve long-term goals.

These examples show that funding’s impact depends not only on the amount, but also on whether it reaches communities directly and treats them as equal partners in shaping solutions. Even with the best intentions, power dynamics are still at play. But funders can level the playing field by ensuring they are aligned with the goals Indigenous communities set for themselves. “When you have the same goals and you’re strategizing together, being totally transparent about what’s happening, that’s a different kind of relationship than most donors have with grantees,” David Rothschild of Nia Tero said. “We’ve learned that achieving that kind of relationship is about being authentically present, being with them on their journey and ensuring that our vision of what we want to do matches theirs.”

Dig Deeper

The Solutions Insights Lab spoke with community groups, funders, researchers, and more leaders working on climate action to uncover these patterns and insights. Explore those conversations.

Explore a map illustrating connections among organizations engaged in climate action. Locations are approximate and not intended to represent precise addresses.

Interviews:

News Articles:

From Barita News Lumbanbatu / Mongabay: Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago (AMAN) is …

From Maxwell Radwin / Mongabay: Amazon Conservation Team partners with indigenous and other local communities …

From Fabio Teixeira and Laurie Goering / The Japan Times: Conexsus provides financial, technical, and …

From Emily Chan / Vogue: Canopy’s mission is to protect the world’s forests, species, and …

From Fermín Koop / Dialogue Earth: Global Methane Hub accelerates action by governments, civil society, …

From Isvett Verde / The New York Times: Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC) is …

From Louise Hunt / Mongabay: Kaleka is an Indonesian, non-profit organization that strives towards the …

From Juan Francisco Ugarte / Salud con lupa: Ecoan is on a mission to conserve …

From Ayenat Mersie / Devex: Green Climate Fund is the largest global fund dedicated to …

Explore More Insights