Industree Foundation works at the intersection of equity, gender, and climate by focusing on training women to adopt green business practices using sustainable natural fibres and regenerative agricultural value chains, and connects them with markets for natural and biodegradable products.

Neelam Chhibe of Industree Foundation spoke with Lissa Harris on December 11, 2023. Click here to read the full conversation with insights highlighted.

Lissa Harris: If you could start off by introducing yourself and your organization, and talk a little bit about the problem you’re addressing and how you’re addressing it.

Neelam Chhiber: I’m Neelam Chhiber. I’m the Co-founder of Industree Foundation. We work at the intersection of equity, climate, and gender. Our focus is on traceable supply chain, essentially, and looking at economic empowerment as a pathway of social transformation of women. Our economic empowerment approach is built around value chains, and the value chains that we work on are climate-positive. That’s how there is a very direct link between climate and gender. The equity piece comes in because we help build women’s collectives. Women take ownership of the value chain via their collectives, and this model is built on a fundamentally government program.

The government has millions of women in Indian villages who are formed into self-help groups, and then these are further collectivized into producer institutions. You could call them small co-ops. It’s a means of creating rural livelihood. This is a program run by the Government of India, the Ministry of Rural Development, National Rural Livelihoods Mission. And therefore we have access to maybe 40 to 50 million women in the country, who could conceivably work on climate solutions, at the same time, building economic prosperity for themselves and their families. In short, that’s the space we are in.

Lissa Harris: Who are your direct beneficiaries, and how do you serve them or work with them? How do they benefit from your work?

Neelam Chhiber: Historically, we’ve built our model working directly with women. That’s what we’ve done for the last 25 years. We have helped women form the collectives. We have helped them build their markets by supplying to global supply chains like IKEA, and we have enabled them to get access to regular income, Social Security, and moved them from an informal workforce to a formal workforce. Ensuring there’s no forced labor, no modern-day slavery. And we’ve done this at scale.

I think the proof point necessary was that these collectives and these women need to reach self-sustainability, so that once we are no longer there, the collectives survive. We’ve proven that point with direct work with communities in four states of India, and now we’ve opened out the model to enable others to do it. Because we don’t see scale happening by us doing it. When we did it, we call it deep hand holding. It takes us three to five to seven years to help a collective attain self-sustainability. We talk about these enterprises of women being SMEs [small and medium sized enterprises]. They could be SMEs of 300 to 500 women, but they are collectives. And ownership and leadership emerges from within the women. SME is a term well-known under the Ministry of Industries in India, so we are trying to mainstream the idea. We are saying that these are not collectives on the fringes of society, but these become manufacturing or plantation industries. Our organization is T-R-E-E, and then the other way, it is called T-R-Y.

We are really talking about mainstreaming. India has a huge issue with job creation, and India has a dismal women’s labor force participation. The three key issues in India are jobs for all, because we are seeing jobless growth. I think we are going to grow at about 7% this year, but it’s jobless growth. Because the more automation there is in manufacturing, the less jobs there are that are created.

We find that the poorest communities in Indian villages cannot really all scale through IT. The Indian economy has grown a lot through services, IT, digital, but we find that in rural areas, it’s very tough to mainstream that way. Manufacturing and plantation is inescapable, so we now build women’s collectives who plant regenerative material, like bamboo, which is also great at carbon sequestration. And then, we work on regenerative enterprise. That means value addition to the raw material resources that surround the villages, which creates a lower carbon footprint, and which enables prosperity. The voice of the women in the community is heard. There is this long-standing discussion and discourse that when women earn, you see improved nutrition, improved health, improved education in the poorest families. So, we address a number of Sustainable Development Goals through this work.

Lissa Harris: How do you work with government programs? You’re serving women directly, but how do you do that work in partnership with the government?

Neelam Chhiber: By serving women directly, we built a framework of action. It’s called the 6C Framework. When we go to the government, we have a toolkit that if you do these 6Cs, and we have a capacity stack. Some women in the collective who are less educated or who are more interested in the manufacturing aspect, will do the manufacturing. The women who are slightly more educated or have slightly stronger entrepreneurial abilities, they go into paraprofessional roles. They go into managing quality, managing productivity, managing HR. Because you have to keep track of wages, you have to keep track of so many things. You have to keep track of raw material flow, wastage, etc. Because these are small manufacturing businesses at the end of the day.

Then, further up, you can have women enterprise leaders. You can have women who sit on the boards of the collectives. We’ve got a capacity stack. Taking a few of these toolkits, which all fall within the 6Cs, we then now work with State Rural Livelihood Missions. The National Rural Livelihood Mission comes under the Ministry of Rural Development at a national level. India, as we know, is divided into states, and each state has their own mission. We engage with the State Livelihood Missions, and for example, Karnataka has already got like 100 collectives of 300 women each. We’ve been asked to work with 30,000 women who are across multiple value chains and enable their enterprises to become self-standing, give the women regular incomes, access to market, access to the proper techniques to reach those markets.

That’s how we are working now. Going forward, we will be enabling the manpower in these State Livelihood Missions to do what we do. So then, they can roll out some of these capacity stacks through the missions.

Lissa Harris: What makes your approach distinctive from other organizations that are working in this space, that are working on similar problems? What makes you different?

Neelam Chhiber: I think what makes us unique and different is our experience, our belief, and our complete conviction that all this needs to be market-driven. There is no income, there’s no livelihood, there’s no economic empowerment, there is no ability to adapt to climate change without having markets which will purchase from you, from these collectives. We are extremely market-driven. Our entire 6C Framework is built around markets, with a huge focus on design, huge focus on what the market wants.

Lissa Harris: At the same time that you’re working with the government and you’re working with women in rural villages, you are also working with corporate partners to develop those markets for the products in this supply chain?

Neelam Chhiber: Absolutely. But not just corporate players. Like I spoke about the capacity stack, there’s also a channel we call market channel. There’s a channel stack, so most co-ops and collectives have to start with local markets. Then, you go to regional markets. Then, you go to national markets. As your quality improves, then you go to global markets. Because the demands of these markets increase steadily, the pricing positioning is at the highest where ESG [environmental, social, and corporate governance ]matters. A lot of this will eventually kick into environmental, social, and corporate governance buying and ESG commitments of the larger corporations. But over the three to five-year horizon, they’ve got to move up the channel stack. So, it’s done in a very graded fashion.

Lissa Harris: Is there a particular example that you can share that shows the impact of the work that you do?

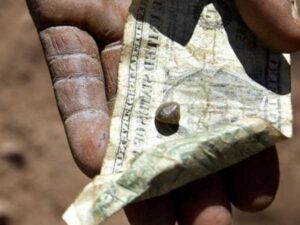

Neelam Chhiber: Definitely. We do regular social audits. We have a collective called GreenKraft, which is being funded by USAID. It has over 3000 women, and it’s been working in the banana bark value chain. It’s been supplying banana bark home accessories to IKEA and globally. I can share that with you, but we see a lot of first-time women earners. We see that more than 50% of the collectives are single women who actually have no access to any other forms of income. We see a lot of women just have to move a kilometer or two from their space of work, because these are all the issues that prevent women from working. There’s no elder care. There’s no child care in India. We see a lot of women who choose to work from home. Because there’s a huge issue with global value chains on child labor, when women work from home, we have to prove to them that there has been no child who’s [been involved]. We built a system to make that happen. I can share, of course, the numbers with you in more detail, but we see income increase of more than 30 to 40%. In some cases, we see a tripling of income.

Lissa Harris: What are some insights or teachable lessons that could be taken from your work, that other people working in this space could use?

Neelam Chhiber: I think now, we are seeing scale through a bamboo value chain. It’s a bamboo plantation. Finally, after 30 years of work, we found that the most replicable of our work by governments and by other countries, other geographies also, is the regenerative plantation piece. Because there’s a very direct connection to carbon credits as a form of income for communities, over and above the commercial sales of the raw material they produce. We are finding particular value chains to be very easy to replicate, bamboo being one of them. We have a $15 million innovative finance instrument. We are just closing on March 24. Then, we are looking at a $100 million discovery of that in India, across multiple agro ecological zones of bamboo, where we are looking at impacting more than 100,000 women farmers.

Now, we see that this is possible in most countries of Africa. We see it possible over Latin America. We see it is possible in island nations. As a lot of companies head towards net-zero in construction, Sweden is looking at building entire cities out of fabricated wood. There’s a lot of research happening, because the third-largest emitter of carbon on the planet is cement. After the US and China, the third-largest emitter of carbon is the cement industry. Moving away, it’s like this complete attachment to fossil fuels. People are going to have to unattach themselves from cement. So, certain raw materials of the future that are natural, but have huge potential. Look at all the throwaway toothbrushes that every hotel has. Now, it’s plastic toothbrushes or plastic combs when you walk into a hotel.

Essentially, saying that certain value chains, per se, are just easily transferable, but with relevance to local geography, local communities. At the same time, at the other extreme is the value-addition enterprises. That is also transferable, slightly more complex. We’ve been at work on something called the Society Platform, which should, ideally, over the next five years, have the techniques and methods for all communities to do what we do. That’s a little way off in the making. It sounds very abstract, but we’ve been working on this for quite some time. We do believe if a bunch of tech tools are created, which tech is not going to solve the problem, but if communities are given access to more and more tech tools, a certain amount of standardization that is required in the global supply chain will be easier to make happen within the local context. We’ve been working on a Society Platform to make that happen, but that’s a little further down the way.

Lissa Harris: I wonder if you could talk about how you measure success. What is the evidence that you’re making progress? And in this realm, I guess I’m curious about success in the realm of economic development for rural women. Also, since we’re talking about carbon markets, how do you measure the carbon benefits of your enterprises? How do you measure your carbon sequestration, making sure that carbon credits are solid and that sort of thing? You could address that from both angles there.

Neelam Chhiber: On the economic empowerment and the social empowerment side, there’s a very sharp, strong set of indicators that we have, outputs and outcomes that we have worked out with USAID. We’ve been funded heavily by USAID on this journey over the last four years, so there is an entire metric stack that I can share with you. The metrics are, in social empowerment of women, women’s decision-making in the family. Increase in women’s decision-making, increase in her, say, reduction in gender-based violence.

Lissa Harris: Do you do that by surveying the women that are participating in the program?

Neelam Chhiber: Absolutely. There is qualitative, quantitative measurement happening on the gender outcomes, because this is from a gender fund of the USAID. We’ve got very strong gender outcomes, and then we’ve got very strong economic outcomes, increase in income and all of that. We track those two. There is also some amount of equity outcomes, women increasing leadership roles in the collective. Because it’s not just about women being at the bottom of the value chain, but they’ve got to move up the value chain. The whole equity part comes in there. That’s on the social and the economic side.

On the carbon side, there’s a very scientific approach being taken through bamboo. We are trying to prove the carbon case through the bamboo value chain. The reason why bamboo hasn’t succeeded with smallholder farmers? Anywhere in the world, it really hasn’t succeeded. Bamboo succeeds in large plantations. It succeeded in China because China worked on backyard plantations. Meaning, every family just grows a little bit of bamboo. That’s why they’ve been successful. India has got 140 million smallholder farmers. They’re asking a farmer for just 0.3 acres of land and just giving them 60 saplings. Every 0.3 acre of land is disparate. There’s one here, and then there’s 1.3 acres three kilometers away. Then, there’s 1.3 acres three kilometers away. But everything, all the data is aggregated into clumps of 10 acres, 20 acres, because these are India’s first Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified plantations.

Historically, people have said FSC doesn’t work with so much of disaggregation, but the fact that every plot is geo-tagged, every plot’s soil is tested for carbon before plantation, and then the bamboo growth, and even now there’s research going on because we are planting about six species of bamboo. We are working with forestry colleges on very specific carbon sequestration of different species. There’s very generic data out there that you get 17 metric tons from one hectare. They’re trying to drill down and get more specific. Then, it’s not just the carbon, the bamboo sequesters, it’s also the soil. Because all this has to be vermicompost, and there’s a bunch of other factors.

At the end of the day, we are in the process of making a very strong case that we should be getting about close to double the amount of carbon sequestration as is what is normally mentioned through research already done. All that is happening in parallel on the carbon side.

Lissa Harris: I wonder if you could talk about challenges. Every social innovator learns as much from things that didn’t work as things that did. Is there an example you can point to of something that your organization tried that didn’t work, that you learned from?

Neelam Chhiber: Absolutely. What didn’t work is, we tried mixed groups, men’s groups and women’s groups. It never worked. Because the men always just took on leadership, which wasn’t very helpful. We now work almost with 100% women’s groups. We do work with male farmers. Bank accounts in the collective are open in the names of the women. Land is owned by the man, but all income from the bamboo goes into the woman’s account. We don’t want to exclude men, definitely, because men play a very critical and pivotal part in gender equality of any kind, but we have to constantly look at the shifting of power. That’s one thing that we learned from our challenges.

The other thing we definitely did learn? That value addition enterprise, because we started at the tough end of the stick. We started with value addition, and now we move to a plantation. We find plantation is easier to spread the 6C Framework on with everyone. Then, if you get the principles of 6C, that even if you plant bamboo, you plant a species that the market wants, you just don’t plant any old species. Obviously, you do FSC because the market wants FSC. If we can, and obviously when they have to sell the raw bamboo columns, they’ll have to work with the market in what shape and form the bamboo goes out. So, we believe that.

I think we were very challenged when we tried building scale through value addition or regenerative enterprise. We are finding that pushing the model out through regenerative plantation will make it an easier pathway for communities then to build regenerative enterprise on top of that, if you can understand what I’m saying. Sometimes, it’s very tough for people to do the toughest thing in the beginning. So, start with the simpler thing and then move on to the value addition piece. But for communities, value addition should lie at community level. But we’ve said, let them first supply raw material to other people, to normal, small, and medium enterprises. The capitalist system lets them learn to supply at least raw material. Then, they can look at setting up enterprises for finished goods.

Lissa Harris: And they work upwards in complexity? They get experience?

Neelam Chhiber: Yes, absolutely. It takes a long time for communities to understand urban or modern market professionalism. If you can just start it in a simpler format, it’s easier.

Lissa Harris: Just to expand on this issue of challenges, setting aside the issue of funding, because everyone struggles with funding, are there challenges that you’re running into that you haven’t yet been able to solve?

Neelam Chhiber: I would say scalability. I would always say scalability. Because opposition to work, I believe if you’re really a community-driven organization, it’s a question of how you engage with communities. There’ll always be opposition in communities. The farmers laugh at us and they say, “You just take 10 acres from us. Why do you want 0.3 acres from 30 of us?” But we say, “No, it’s high risk if we take 10 acres from two of you.” We always go in and we explain and we solve, and I think that’s the backbone of our organizations. I don’t think challenges on the ground are an issue. They’re always there, but if you can’t surmount those, then you are not a grassroots organization. I’ll put that to the side.

Scalability enters another realm, and it’s a very important realm that we do not definitely want to scale. We know we can’t solve for the problem by upskilling. We’ve understood that scale will come through networks, co-creation, and tech tools. That’s the definition in our work we’ve done around Society Platforms. We’ve built networks. We’ve got two very strong networks, and tech tools are getting built as we speak. But definitely, and this is not a standard funding complaint or a standard funding issue, it’s linked to scalability. Forget normal organizations, forget normal project-oriented organizations facing challenges with funding. For scalability, where you don’t want to do it in a normal project way where you’d scale just your organization, the opposition to financing scalability through networks is humongous. Because there’s a complete lack of understanding on how that could even happen, if you know what I mean. It’s a new way. It’s a new path that you’ll scale through networks. You’ll scale through training the government. Who is ever going to fund you to train the government? You understand?

Lissa Harris: The challenge is getting investors or people that would fund your work to buy into the idea of…

Neelam Chhiber: Of scaling in a different way. That’s the challenge. That’s what I mean by scalability, not just the challenge from the fund. Because it’s a new way. I don’t think there’s been too much of scale that you’ll see which is really filtered down to grassroots that’s come out of huge networks. It’s a new domain. A, there’s the funding side of it, and B, organizationally, again, it’s a challenge. Because most people in our sector, like I explain to my teams, all of us in our sector think in verticals. Bamboo vertical, millet vertical, rice vertical, fashion vertical. You can build a project on it.

I’ll train so many women, they’ll make so much product, sell, whatever. But when you talk about scalability, you have to do a lot of horizontal thinking. What are the horizontals that go across all value chains? We believe the 6Cs go across all value chains, but they’re horizontals. This is what my teams tell me, that the funding for horizontals is very weak as compared to funding for verticals. Because in verticals, you directly address the community. You asked me the question, right? “Do you serve a community directly?” In verticals, you serve communities directly, but horizontals, you serve communities indirectly. But without the horizontals, scalability is tough.

Lissa Harris: Can you talk a little bit about how you’re working to advance system level change in your field? This touches on the idea of networks as well and scaling through networks.

Neelam Chhiber: Systems level change? To us, we are actually going through a Co-Impact Design Grant, this whole thing around systems level change, as we speak, which I’m not participating in, which my organization is participating in. I don’t know how much of this articulation of verticals and horizontals has been done or understood, but to me, systems level change is all about working in horizontals, where you cut across because impact on communities happens vertically. It has to happen deep. You have to go in and touch everyone, but a single organization can’t touch everyone. Multiple organizations have to touch, so they all have to be trained in a horizontal format. We call it deep hand holding and then broad hand holding. Then, there’s something called light hand holding, which is on the top of it all. To simplify it, for us, what we’ve started saying is, there’s a demand side, there’s a supply side. Supply side are the communities. Demand side is anybody who’s going to buy from these communities. You’re going to develop the supply side, you’re going to develop the demand side, and then you got to develop the finance side. Now, we’ve actually narrowed it all down to three, from six.

Lissa Harris: What do you think is most needed from other actors or partners to advance systems level change?

Neelam Chhiber: In economic empowerment, it’s very clear that you will not be able to do any systems level change without all three actors; civil society or social organizations or organizations that connect to community, governments, and markets. These are our three key players. Without this, nothing is happening in economic empowerment, without all three. Especially in a country like India.

In Africa, the government doesn’t have that many schemes for economic empowerment, but India has a lot. India has obviously got some more money than a lot of African countries. I’m just coming from Africa and there, the government schemes for economic empowerment are not huge. India has got huge government budgets, so those can’t be ignored. They have to be put to use. What is needed from other partners? From civil society or other actors, obviously they become part of networks through which we work, but definitely what is needed is far more trust. There’s a huge lack of trust.

Lissa Harris: Lack of trust of the women that you work with?

Neelam Chhiber: Lack of trust for each other. Because in civil society, everybody is in a competitive mode, so they don’t trust each other. Understanding that unless we work together, we are not going to unlock capital for everyone, I think that is a huge limitation which needs to be overcome. That, to me, is actually the only limitation. A lot of civil society actors have developed and grown with a slightly individualistic philosophy. How much of that do you cut across for the greater good is going to be the question.

What’s needed from the private sector is that unless they are evaluated on a triple bottom line, we are not going to see a deeper interest and engagement in them. None of this community action or none of this economic empowerment will happen without co-creation between the communities and private sector. Because it’s a give and take. Right now, there are very few private sector people who have the patience to change the ways they work, or even be a little more understanding of the growth curve of a community. I’ll put it like that. We’ve had a 12-year journey with IKEA. H&M gave up after two years. They said, “Oh, this is too complicated. We can’t do this.” Okay, so that’s it. That’s going to be a huge issue that the private sector will have to change on, and they’re not going to change unless their incentive methods are changed.

Now, we come to the government. Government may actually be the easiest one to crack on simpler supply. Bamboo? Government is jumping. They’re saying, “Let’s do it. Let’s do it. Let’s do it.” Because it’s simple for them. I just think with the more complex things, it’ll get complicated, but governments have to deliver on job creation and income creation at rural level. They’re deeply interested. What would be the limitation there? I think it would be the flow of capital, for which there is a solution. You got to work on social impact bonds. You put the money up front. Their money will crawl in slowly, it’ll be delayed. But meanwhile, work keeps happening. It can be more outcome-based financing, and I think that should work.

Lissa Harris: How do you see your work evolving over the next five years?

Neelam Chhiber: Over the next five years, I think we will scale up bamboo tremendously in India, and we’ll be able to seed it in two or three countries in Africa and two or three countries in Asia, other than India. I see that maybe after three years, we could see the beginning of the scale of regenerative enterprise, after another three years. But I would see regenerative plantation to be reasonably scaled for all the toolkits to be in place to move to other value chains other than bamboo. For example, seaweed. Hugely carbon sequestered and hugely income-providing for marine communities. And hugely nutritional. There are a bunch of other value chains. You can take linen. You can take cotton. But we will scale bamboo and then we’ll be able to use these in other value chains.

Lissa Harris: Is there anything that we didn’t cover that you thought was important to add or to expand on?

Neelam Chhiber: There are very, very few organizations globally who are really looking at economic empowerment as a linchpin to women’s social empowerment. Industree does that, and Industree, I think, has made some of the strongest links between gender and climate, saying that women are not going to be victims of climate change, women are going to be mitigators. Women from the poorest communities in the world are going to be some of the strongest mitigators and adapters themselves to climate change. That’s what I’d like to see. I also think it’s a little important that we expand on the measurement and evaluation piece, of which I’ve given you just a very threadbare thing. I think that I haven’t done justice to that part of it, the impact part.

Lissa Harris: Wonderful. I want to thank you so much for taking the time for this today.

Click here to read the full conversation with insights highlighted.

Lissa Harris is a freelance reporter and science writer (MIT ’08) based in the Catskills of upstate New York. She currently writes about climate, energy, and environment issues from a local perspective for the Albany Times Union, her own Substack newsletter, and various other digital and print publications.

* This interview has been edited and condensed.

Learn about other social innovation insights that include training women.