Landesa helps families in India obtain legal land rights through digital records. Supporting women to lead the documentation work has been a breakthrough strategy.

Chris Jochnick of Landesa spoke with Alec Saelens on November 2, 2023. Click here to read the full conversation with insights highlighted.

Alec Saelens: Can you describe the problem that you are addressing with Landesa and how you are responding to that problem?

Chris Jochnick: The problem is both simple and complicated. Most of the people living in poverty today share three basic facts. One is they’re rural. Even though there’s a lot of urbanization, they live off the land and, second, they don’t have a secure title to the land. If you don’t have a secure title, then it’s much harder to invest for the long term because the land can be taken away from you and you can’t leverage it for government services or credits. [The third is] if you’re a woman, the situation is even more dire because even where there are laws that may protect women’s rights with respect to property, in most countries still women are treated as second class when it comes to land. For purposes of inheriting it or managing it or owning it, they’re at a big disadvantage and that makes things that much tougher. These are the main issues that we look at.

The root of the problem is that a lot of countries, especially post-colonial countries, have never gotten around to titling land. Throughout, for example, Sub-Saharan Africa, something like 90% of the land is still not titled, which means that people are living on it and using it, but in a precarious situation. We work with governments that are willing to and interested in addressing that legal challenge. We help them by providing policy guidance and law reform guidance to strengthen land rights for the rural poor. As part of that, we always have a gender lens to make sure that women are treated equally to men. Increasingly, we work on collective land rights for communities that share their forests or their land communally to strengthen their rights to those forests or those collective areas.

That’s been the work of Landesa. It’s largely work that involves government partners, but we also work a lot with civil society groups that are engaged in a similar struggle usually at the local level. We work collaboratively to try to strengthen land rights. We also do some work with corporations because companies are often a part of the problem in terms of land grabbing and threats to land. Many companies have taken the position that they want to address any possible land conflicts or potential land risks.

Alec Saelens: You’ve described a range of different stakeholders that you engage with, but who is the primary beneficiary of your work and how would they benefit?

Chris Jochnick: The primary beneficiary are women and men who live on land and will see their ownership rights to that land strengthened through our work. That gives them a leg up in terms of feeling more confident to invest in the land and being able to protect themselves against others taking advantage of them or kicking them off the land. In some cases, we’re also engaged with governments to give land back or to prioritize certain people without land, so they get land. Beneficiaries then would be landless individuals who become owners of a small plot of land. Other beneficiaries would be communities that enjoy more secure rights to manage and protect and restore the lands or the forest that they survive on.

Alec Saelens: Could you give me an example that illustrates the impact of your work? What is the most salient effect that you’ve seen, a story that really demonstrates the value of what you’ve been doing?

Chris Jochnick: In India we’ve worked with governments like West Bengal to identify land that’s owned by the state and is not being used in some way. They identify women in particular who are landless, to carve out small plots of land about the size of a tennis court and to give it to those women where they can have a house and a small vegetable garden as the first step towards pulling themselves out of poverty. That would be certainly one type of project that we’ve done quite a lot of, particularly in India. In other cases in China, we’ve worked with the government to strengthen the rights of smallholder farmers to have long-term leases to land. Over the last 25 to 30 years, we’ve seen incredible gains by small holders in China who are now feeling confident to invest in that land. We have worked with the Chinese government for 25 years to continually strengthen the rights of those individuals, which number in the hundreds of millions to be able to invest in their lands and to benefit directly from that.

We’ve worked now in over 60 countries, so in each of them we have fairly similar stories. Our efforts are directed mostly at the macro level, the legal change. We count on other organizations to work more directly with the small holder farmers or the indigenous communities who are benefited. In Rwanda, right now, we’re working with One Acre Fund. We work on the policy reforms and they are working directly with the farmers who should benefit from this work. Our efforts are not so much at the individual level, although we are involved sometimes in titling ceremonies where the government will hand out titles to land and we can see the individuals that are benefited. Our impact tends to be at least a layer removed from that at the policy and legal reform level.

Alec Saelens: Can you give me a sense of the way in which you measure success, and some additional examples of evidence that speaks to the progress that you’re making. What would be the core metrics that you look at in addition to what you’ve already shared about the situation?

Chris Jochnick: We have many different metrics and you can find them on our website. The main metric we look at is how many people, and we break it down by women and men, stand to benefit from legal changes where we’ve had a significant hand or where we’ve played a significant role. That is not saying that they will benefit necessarily or that they have benefitted, but they stand to benefit. The law now has strengthened their rights under law. There are still some steps that have to happen, for example, that law has to be implemented, or there may be other obstacles even where there are strong laws, or there are cultural reasons and norms that people can’t take advantage of those laws, but having a legal right is at least one step in the right direction. That’s the first basic measurement.

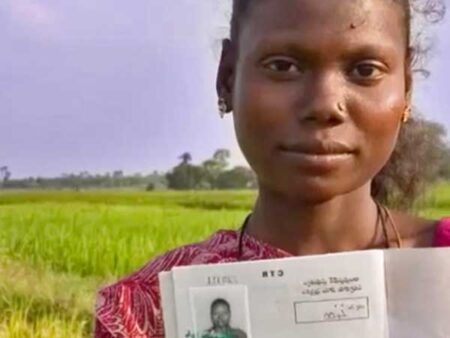

Then we look at how many people have received actual land titles. We’ll also look at how many influential actors have been trained in land rights. Those could be government officials or they could be civil society leaders. In India, we’re working with women’s self-help groups to train members of those self-help groups in how to register land. We work with governments, civil society, and companies to train and strengthen people’s understanding of land rights as well. That’s another thing we measure.

What’s most difficult and what we tend not to measure, although we have done some studies, is how people’s actual lives are changed by the interventions that we are making. That is, I would say, one of the big challenges that a group like Landesa faces. There are some more sophisticated donors that understand the complexities of working at a systems level, but many donors want to see direct and tangible impacts on people’s lives. You can show this sometimes if you’re educating a kid or putting in a water filtration, but it is much harder to do if you’re working on long-term legal change. There we have to look to studies that have been done under similar circumstances to show that under these circumstances, this many people can be expected to benefit from the legal change, but it’s tough to do that in any particular context without being able to do long-term, very expensive, impact evaluations.

Alec Saelens: Could you share a little bit more about what you think is most needed from actors or partners or people that you work with to advance that systems level change?

Chris Jochnick: It’s helpful to have a holistic range of actors working on these issues. Where we play I’d say our best role is at that legal reform level. But even there, it’s helpful to have local actors. We’re an international NGO. We do have offices that are staffed with local experts, but it’s helpful to have local organizations also working on legal reforms so that they can then hold the governments accountable to whatever those changes are and make sure that the government is actually implementing the laws, and that people that are beneficiaries of those laws can actually claim their rights in practice. That means there’s got to be a number of organizations like Landesa, for us to try to address a cultural norm that prohibits women from owning land, even though the law says women do have the same rights. It’s very hard for an international NGO to get involved in that kind of a cultural shift.

We need organizations that work at the local level that have the legitimacy and credibility to be able to work with, let’s say, tribal leaders and that have the confidence of local communities. We need a whole set of partners to be able to make sure that the legal reforms that we try to help move actually have an impact on people’s lives. A lot of different sectors need to come around to understand how critical land rights are. That’s where I’d say Landesa has seen a lot of movement. We got our start in the early seventies when very few organizations were talking about land rights. When we would go into a country, there were very few local organizations that we could partner with. Land rights were nowhere on the global agenda nor featured in the millennium development goals. Now in 2023, land is all over the sustainable development goals. There are organizations in every country working on land rights. The philanthropic sector has sort of come to appreciate the importance of land rights. Now everything we do, almost, is done in partnership with lots of other organizations that have come to appreciate the critical role of land rights in whatever they are, whatever they’re concerned about. Whether that’s food security or women’s empowerment or climate change or smallholder farmer livelihoods. Getting all of those different organizations to prioritize land rights has been a big part of our long term agenda. We really need the collective forces of lots of different organizations to pull this off from start to finish.

Alec Saelens: Considering the positive crowding of this space of folks and organizations that do care about land rights, could you say a little bit more about what is distinctive about the approach that you have to this issue, particularly based on your historical role, where do you stand now compared to where you were before?

Chris Jochnick: I think Landesa traditionally was distinctive because there really were no other organizations, certainly not at the global level, that were dedicated to this issue of land rights as a key factor in the development process. Today, we’re still distinctive by virtue of having worked in over 60 countries. We have a certain collective experience gained over many years where we can bring lessons learned from other countries to any government that’s interested in making these changes. We house probably the largest collection of land rights experts in any organization. We do all the work, we’re not a consultancy. We offer these services free to any government that’s interested in it. We have the credibility of the philanthropic community to provide resources so that we can continue to do that work. I’d say the other thing that makes us distinctive is that we have a longstanding prioritization of women’s land rights in particular that goes back over a decade. All of our work is informed by the importance of prioritizing women. More recently, we’ve built up some experience and expertise around the intersection of land, climate change, and poverty that is also somewhat distinctive.

Landesa is good about working with governments. We have worked with so many different governments of all stripes, many of them very suspicious or antagonistic towards international NGOs. Landesa has always managed to find a constructive way to work with those governments where we work. That includes governments like China and India, for example, where we’ve been for a long time, and more recently governments in Ethiopia or Tanzania. We’ve managed to remain credible to civil society groups, but also to governments. I think that’s somewhat distinctive. Having been around the NGO community for 30 years or so, there aren’t many NGOs that have that sort of depth of experience working with governments.

Alec Saelens: That’s fascinating, let’s drill into that a little bit more, particularly when it comes to your work with governments. Are there any insights that you have for civil society; what is the secret sauce? What’s the teachable lesson? What’s the recipe for success for maintaining credibility and achieving change, while not losing the faith of the governments in your work?

Chris Jochnic: Actually, one of the other tricky governments is Myanmar, where we did work both pre-democratic spring with the military government and then afterwards with the democratic government. We continued to work even post coup, although we finally had to leave Myanmar.

I think the secret sauce, there’s probably a few things. One is an appreciation of the role of government. A lot of organizations still think that they can fix these problems without governments, and that governments are too corrupt or too slow or too difficult or too bureaucratic. Landesa’s belief from the beginning is that governments have a fundamental role to play in this issue, and they have to be engaged no matter how difficult they are. You can always find champions within governments to work with. Having an appreciation for the critical role played by governments and being able to identify people within governments that share the same vision as Landesa about the important role of land rights, is important. To work constructively, which means quietly as we don’t trumpet our work, we allow governments to take credit for things, we don’t need to be out front in whatever. In many cases, governments are not comfortable with the idea that they’re taking policy prescriptions from a foreign NGO, and we’re perfectly happy to take a quiet backseat.

Then I think we bring something valuable to governments. We do a lot of research before we approach governments and that’s so any policy prescriptions are very well-founded and have the kind of legitimacy and credibility that governments feel good about trusting. We have a reputation now of having worked with many governments in a constructive way so they can feel like they’re not going to get burned by us. I think all of that probably contributes to whatever secret sauce we have.

Alec Saelens: That’s fascinating. On the flip side, when it comes to civil society, what’s the secret sauce for engaging them in a way that imbues you with their trust?

Chris Jochnick: In some ways I think it’s similar. We don’t have a need to be out front. We want to be supportive. When we go into a new country, we always seek out civil society organizations to make sure that they’re aware of what kind of work we’re going to be doing, and to make sure that they are supportive of any kind of policy prescriptions that we’re going to make. We’re very transparent about what we do. We listen to civil society groups. If civil society groups are not comfortable for any reason with what we’re doing, we would take that very much to heart. Increasingly, we try to strengthen local partners as part of the work that we do. For example, we provide resources, in some cases we’ve managed to bring new funding in for local partners,we’ve done some trainings with local civil society leaders. I think it’s a mix of making sure that we’re not perceived as problematic. We have to address that risk, especially with local partners and making sure that they see more benefits to our being there and doing the work than negatives.

I don’t think this is necessarily brain surgery. I think it is being emotionally intelligent about how a relatively large international NGO can operate effectively. It does require a lot of strong personal relationships and a certain amount of trust to be built up so that we’re not resisted. Secondly, we can do longer term collaborative work. In some cases that’s quite easy. In other cases it’s more challenging. But we’ve, I’d say, managed to do it.

We’re part of local networks in many countries, and we’re part of the main international networks that have to do with land rights. That helps with each effort we make and each partnership we build, our credibility is strengthened for the purposes of the next country that we target. All of our country efforts are led by nationals of those countries. Wherever we have offices, they’re led and staffed by local representatives. We don’t have any expats leading that work, and they’re supported by our offices in the US.

Alec Saelens: You’re working on a lot of solutions to avert any issues that may come up and roadblocks, but aside from funding, which I know is an important issue in context of social innovation, are there any challenges that you face that endure?

Chris Jochnick: There are challenges, of course. There are challenges in any large INGO. I think maybe the distinctive challenge that we face is that land is still a relatively unappreciated issue. Even though it has taken hold in some quarters, the vast majority of donors are still not thinking about land or appreciating the importance of land rights. Most people in the global north, where the money tends to come from, feel very secure about their land and property rights. It’s hard for them to empathize with this idea that most people living in the rural areas of the global south don’t enjoy those rights, and what an enormous barrier that is. There’s a certain amount of awareness that is still lacking. It’s a complicated issue. There are still all kinds of challenges with strengthening land rights and implementing effective land rights systems. There are governments, and this isn’t distinctive to our work, but they are just very hostile right now to international NGOs. And there’s sort of a backlash in many quarters to international NGOs, which can be challenging. I would say those are the big ones that come to mind.

Alec Saelens: Is there anything that you think is important to convey to others who are in this space, in social innovation, or more broadly about the value of the work that you do and how it came about?

Chris Jochnick: What I was saying about working with governments is really important. I think to do systems change work, it’s very difficult to do that without government partners, and you have to overcome a certain level of cynicism about that. Even corrupt governments, even authoritarian governments are capable of doing good at times and finding those opportunities is really critical. Finding those people within challenging governments that are influential and have the right mindset is really critical.

Being mindful of the power dynamics of being in a privileged position as an international NGO vis-a-vis local civil society partners and how we exercise that privilege is really important. Being mindful of what it means to come into a new country in terms of marginalizing other organizations, either by our presence or the resources that we might suck up or the voice we might start occupying on certain issues. Just being mindful of that because those local partnerships with civil society groups are just so vital. And in order to work constructively, we have to find genuine relationships so that those groups feel like working with an organization like Landesa is a net benefit and are up for that kind of a collaboration. Another one is that addressing problems at the root is a long-term effort. It’s very difficult sometimes to see the impact of that work when it’s going to take five or 10 years.

Any problem, any major development challenge that we face is only going to be solved in time periods of five to 10 to 20 years. People that are going to get involved with those problems have to be willing to at least work with that kind of a timeline. That doesn’t mean they have to be there for that whole period, but whatever their contribution is going to be, ought to be informed by the fact that you’re not going to see immediate results. Sometimes you’ll even see some backward movement, but you have to hold onto this idea that the trajectory is moving in the right direction. And that’s the only way we’re going to get long-term sustainable change.

Alec Saelens: Speaking of the long-term prospect for systemic change and sustainable change, and I imagine this will vary by context by country, but in the next five years, what do you see your work evolving towards or needing to strengthen or focus on?

Chris Jochnick: A lot more of our work, I think, will be done through partnership with local civil society groups, as civil society groups at the local level start prioritizing land rights, and I think they will do that, and they are doing that. We don’t need to be the ones out front working with the governments all the time. It’s better in a way for us to be behind and supporting local partners that will be there for the long term and that have more credibility in many cases with governments. I see that’s one shift that we’re already starting to make at Landesa, finding somewhat of a changed role for ourselves as in some cases, intermediaries, as some cases supporting and building capacity of local partners.Or in some cases doing the work as we’ve always done it. But as part of that, thinking about ways to create spaces for local partners to step up as they’re able to. I’d say that’s the big change, and we’ve been mindful of that over the last five years or so and are already seeing how that’s affecting our work for the better, and how it’s changing us as an organization.

Alec Saelens: That’s fascinating. I think a great point to end on as well. Thank you for sharing your insights with me.

Click here to read the full conversation with insights highlighted.

Alec Saelens is a former journalist who supports SJN and its partners track solutions journalism’s impact on society and the industry. In his former role, he researched and consulted on the connection between solutions journalism and revenue. He is co-founder of The Bristol Cable, the UK’s pioneering local media cooperative. Before SJN, he was a researcher and coach for the Membership Puzzle Project and an analyst for NewsGuard.

* This interview has been edited and condensed.

Read more breakthrough strategies in social innovation.