Crisis Text Line provides free, 24/7, text-based mental health support and crisis intervention. Users can send free and confidential texts and be connected to trained volunteers who can help them with mental health struggles.

Dena Trujillo of Crisis Text Line spoke with Catherine Edwards on April 12, 2023. Click here to read the full conversation with insights highlighted.

Catherine Edwards: To get started, can I ask you to introduce yourself, your role in your organization, and then tell me a bit about the problem that your work is addressing?

Dena Trujillo: My name’s Dena Trujillo. I am the CEO for Crisis Text Line, and I am a non-founder, but I took over a few years ago. Prior to that, I was with the Omidyar Network, supporting Pam and Pierre Omidyar, who’s the founder of eBay, for 17 years, and working at taking their billions to make the world a better place. I now have the pleasure and honor of running Crisis Text Line.

We are really a mental health emergency route via text and chat. You can imagine people come to us for everything from loneliness and depression to eating disorders, they confide in us. We have thousands of volunteers, we reached over 59,000 volunteers that connect with the texter in their moment of need.

Catherine Edwards: What kind of people does your work end up helping?

Dena Trujillo: Last year we supported over 1.3 million conversations, that’s 4,000 conversations a day. Right now, Crisis Text Line focuses on the United States. Our technology platform can go into the technology backend of our partners. Most of our texters are young, 75% are 25 or younger and 14% are 13 and younger in the United States. The biggest issues for them are relationships, depression, and anxiety, and we’ve seen an increase in loneliness and isolation now that COVID is over. It is about helping those people that are text to move from a hot moment to a cooler climate, to reframe their strength space in that moment, to create a safe space.

Catherine Edwards: Can you talk me through what’s involved in this process? How does it work, first, from a logistical point of view, and also making sure that people have the number to text?

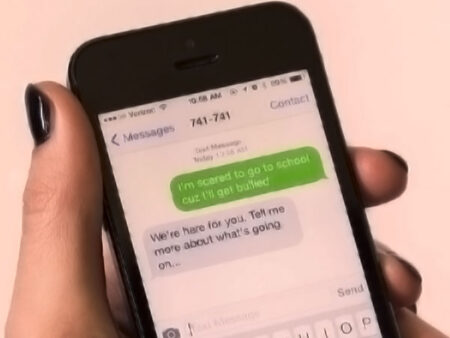

Dena Trujillo: When people text in to 741741, they are connected to a volunteer. We have a triage of volunteers working in the background so that they can identify when somebody is at imminent risk of harming themselves or others. If there happens to be a queue, they go to the front of that queue and are connected with a live volunteer. While we use AI and machine learning for things like triage and helping our staff, connecting to humans, because we are human connectionists, is important in that moment of anxiety, stress, and depression.

We have supervisors, trained clinicians, overseeing every single volunteer conversation. That’s one of the things that makes our model special, is we, in a given month, have about 6,000 volunteers that give their time. Last year, we had 15,000 over the year, and we’ve trained 59,000 volunteers just in the US. They take 30 hours of training, and they learn skills like listening, empathy and deescalation. From a quality control standpoint, we have supervisor clinicians overseeing every conversation, and they are able to provide feedback. A volunteer can raise their hand and ask for help to make sure that every texter is getting the best possible support at that moment.

One of the things that makes us special is that we collect anonymized trend data, so that we can help our partners. We partner with universities, nonprofits like the Boys & Girls Club, and for-profit organizations. It’s how we reach folks, it’s how we get into the community. On TikTok, or Xbox, or Gears of War video games, they can identify people who are in trouble. Our partners send us people, and then we’re able to report back to them totally anonymously. Our customers are your students, who are reaching out to us. They’re experiencing eating disorders, or more anxiety, or financial insecurity. We provide in the moment something like an emergency room.

Our latest research, which is really exciting, shows that our volunteers are becoming more resilient and helping our communities become more resilient. Two-thirds of our volunteers say that their mental health has improved as a result of being a volunteer, and 90%, nine out of 10, say that they utilize the skills they learned from being a volunteer to help their family, their community and their coworkers. When we look at how we solve this mental health crisis that we have as a country, part of what we realized we have to do is help put the tools, that resilience agency, into the hands of as many people as possible.

Catherine Edwards: It sounds like the volunteers don’t have a background in therapy or anything like that. Are they average people from the same communities as the texters?

Dena Trujillo: Yes, volunteers are average people. 55% of our volunteers are under the age of 24. They’re looking for tools to help themselves and help their friends. The volunteers are everyday people, and that makes it more powerful, really. Of course, we have workforce shortages all over the world, and the problem is, mental health and loneliness epidemics are growing faster than we can grow mental health workers. We are now realizing that this volunteering is a part of the solution of how we spread these skills to more and more people. We reduce the need, but also make sure that we have skilled people that can provide empathy, active listening, and skills around deescalation and risk identification that are out in the community, so we can all be safer and get the support that we need.

Catherine Edwards: You have already touched on this, but is there anything else you’d like to add about what makes your work distinctive from other approaches to the mental health epidemic?

Dena Trujillo: One, using text allows us to reach more people at scale. If you look at most crisis lines, they’re one-to-one, one human on a phone or on a text line with one clinician. Even if they have a volunteer, it’s still one-to-one. We have 20 volunteers being overseen by one clinician. That works because it’s text. We utilize machine learning to help with triage, so we utilize technology to make sure that we have humans in contact with each other at scale. So, one is the use of technology.

Two is that our use of data is totally anonymous, de-identified, to make ourselves faster and have higher quality support. We can scale and move faster to meet the needs of and support more people. We have research that can contribute to the patients, that we can give to other players in the space, so that we can lift all ships. The technology, data, and research.

The third arm that really makes us unique is from a volunteering standpoint, it is the skill building that happens for our volunteers, and we can do that at scale. We’ve trained 59,000 volunteers, and we are looking to get to 100,000 so that we’re able to create mental health advocates and mental health warriors, whatever we want to call them, in their communities.

Catherine Edwards: I have a question about the choice to use texting, because you mentioned it makes it possible to do it at a bigger scale, because it’s asynchronous. What are the other reasons to choose that?

Dena Trujillo: One, generationally, younger people are less likely to call. While we support people of any age, we’re really built for young people. Texting is important because it’s a technology that young people are used to and are much more likely to reach out through text than by calling. Text also allows us to reduce unconscious bias. We all have unconscious biases that we can’t get rid of. You can reduce them, but you can’t eliminate them. Having a text exchange reduces the bias and increases the ability to just meet them where they are. It also allows us to have that real time feedback. If you’re on a phone call, you have to evaluate how you can support after the fact. If they’re texting, our clinicians can provide real time feedback. The final benefit is that it helps us be able to do research and collect data and feedback.

The most important thing is meeting people where they are. If you’re in a true mental health crisis, then speaking is actually harder than writing. That is something that we hear and see time and time again. Some people think that sometimes texts are impersonal or might not be as effective, but third-party academics such as Maddie Gould, who is a famous suicidologist, and her team at Columbia have done skilled quality research, and she has said that our conversations appear to have the equivalent impact of a therapy session.

Catherine Edwards: Do you have any metrics for success, or how do you assess how well it’s working or where improvements might be needed?

Dena Trujillo: 21% of our texters complete a post-conversation survey and in that survey, they’re able to give a satisfaction rating. We ask some specific questions that are in line with health diagnostics, as to how they shifted from how they were feeling at the beginning of the conversation to the end. They’re also able to give direct feedback. We analyze all of that. We also take about 1% of our conversations and do quality assessments with our rubric and then we have third-party assessments come in and evaluate the conversations. For example, the Maddie Gould research I mentioned.

Part of what makes our data unique is that our volunteers that are supervisors tag every conversation, and those tags enable us to have insight in a way that’s valuable both for our operations and for sharing insights. During COVID, we were able to send reports about changes in mental health to the officials coordinating COVID response in states throughout the United States. Our feedback was in real time, rather than a year or more later like most mental health research. We have the data, the texting and the tagging, so we’re able to have real time trend analysis. We have crisistrends.org online, which is a place where we have the publicly-available trends data for folks to look at.

Catherine Edwards: Can you think of any examples of trends or insights that have surfaced from the data that were particularly useful? And also any examples of the impact that it’s had?

Dena Trujillo: We have a university partner that recommends folks to use our text line. It’s like a co-branded line. They also let their students know that if they’re in criss, they should text us. They then get that trend report at the end, and I was reading the trend report. They were glad to see that their students over-indexed as compared to the rest of the country, relative to the amount of Hispanic and Latinx texters that were texting in for support. They over-indexed by 40% around issues around financial insecurity. Our university partner had no idea, so now they are increasing their programming for their Latinx and Hispanic students, and increasing their programming around financial insecurity and how they can support their students in this time. Tangible, real information can change the programming that they provide students and customers.

We did research on the impact on young people during the height of COVID, that couple year period, and we looked to see what they were experiencing that was different. One of the things we found was around resilience. Everybody knows there’s a mental health epidemic right now, and so don’t just give depressed people the diagnosis of the problem. We need to provide solutions and resilience. How can people leap in and find agency and hope?

One of the things that we found is that music is profound for young people across every age group. The listening and engagement of music is the number one tool that people find to be effective to support their mental health challenges. That is something we found that we’re trying to share. Right now, there’s a real increase in loneliness, isolation, challenges with relationships, and increases in bullying. The skills around interacting with other humans are really challenged for people right now. We as a society have so much work to do around helping people learn how to have healthy relationships.

Catherine Edwards: Do you also work on trying to affect system-level change? How are you working towards that?

Dena Trujillo: We alone cannot solve the crisis for young people or for anyone. We focus on partnerships and lifting up the whole ship. Partnership and interfacing with federal and state governments so that we can provide our technology backend to organizations, we help to do co-branded lines, we can share our research so that everybody can do a better job of meeting the needs of their community.

We are now realizing the impact of our volunteers. We’re scaling our volunteer programs so that we have more people in communities and in offices and in school rooms that have these skills. We’re also working with the programs to help provide training and their field hours. We have more and more social workers that are trained in doing online mental health support, and have our specific brand of volunteering. Overall, it’s still, how do we spread the technology so everyone can benefit? How do we share data and research so that people can learn and apply to their constituents? How do we help make nonprofits and governments more effective by skilling the workforce?

Catherine Edwards: Which other actors would you say need to get on board in order for these changes to happen? Are there specific people to target?

Dena Trujillo: One of the reasons we’re expanding globally is we’ve spent tens of millions of dollars creating our technology platform. We know there’s never enough funding for this kind of work, so we don’t want others to have to start from scratch and develop this technology. We’re trying to spread that and provide it for other partners around the world. Part of it is people realizing that text is just as effective as the phone. Realizing that you can scale, everything doesn’t have to be one-to-one. That you can use volunteers. It doesn’t have to be all clinical staff. These are the simple things that people, governments, and nonprofit people don’t believe, but studies are showing that it’s true.

More and more we use AI and machine learning to augment, never to replace people, but to help improve training, to help improve data and resources. What we need is people to provide more funding, work with us and others to really utilize the technology and resources we have at hand, and pay attention to the research and data so that we can provide a better service.

Catherine Edwards: Aside from the funding, what would you say are the major challenges when you’re doing this work? Perhaps that was something that you’ve already faced and overcome, or anything that you’re grappling with at the moment.

Dena Trujillo: As you know, funding is always a big challenge. Generally speaking, when people are in the social sector it’s often because we want to collaborate. We are really delving into collaborating, but it takes time and it takes trust, which is built over time. The biggest thing, honestly, is really marketing and getting the story out, because there’s so much competition for people’s eyes and attention. We’re supporting 4,000 conversations a day. We know there is a need because every time we have a campaign, when NBA Cares puts our number on the screen, we see it’s a real need. What that tells us everywhere, there are people suffering, but they don’t know how to reach out to us. They don’t know that there’s nonjudgmental, caring people available to talk to them 24 hours a day, 24/7. The big challenge is helping people know when and how to follow us.

I’m constantly telling people, “Get your phone out, program in your contact list Crisis Text Line 741741, and do it in all your kids’ phones, your families’ phones, because you never know when you’re going to be so in need or so upset, so depressed, in the middle of the night or at a party, feeling lonely and isolated, even though you might be surrounded by people.” We need to let them know where they can reach out, to have it in their phone, and to reach out when they need us.

Catherine Edwards: How do you explain to people how they can know if they’re in a crisis that’s worthy of texting the line?

Dena Trujillo: One of the challenges with our brand is that “crisis” makes it sound so serious, and the reality is, only about 20% of our conversations are directly related to imminent self-harm or harm to others. 80%, they’re serious, but it’s more preventative. And it is just as, if not more, important to get in contact with people in that early stage. We have kids, 13 years old, who are terrified about telling their parents about a bad grade they got on a test, or a boy is not texting them back, and they’re just absolutely totally distraught about this. This is very real for them, in that moment, just as when at a party, there’s peer pressure to do drugs, and they don’t know what to do, or they’re struggling with substance abuse or eating disorders. These kids are able to reach out when they don’t know what to do. When they are sad or lonely, and feeling a little desperate, and don’t know what to do. That is when they should reach out.

Catherine Edwards: What are the key insights that you’ve learned through the years of doing this work, and having access to all the data? Are there any key things that people should know if they’re also trying to get engaged in this field?

Dena Trujillo: We all have our own adult challenges and have loved ones and friends and family that are struggling. Everybody should program in our number or somebody else’s number, but have that resource available and share it freely. That’s number one. Two, don’t be shy to reach out. It really is about reaching out. Three is, volunteer. People are always asking, “What do I do?” By volunteering, you learn the skills. Every volunteer is given a script, so just by taking the training you learn how to support yourself in your moment of need. If there is one thing to shout from the rooftops, it is please make sure your family and friends know the number. And two, do the volunteering, because everyone needs these skills.

Everybody has things they’re holding inside that they don’t share with their friends or their family, and only 28% are getting any kind of formal mental health support. 28% are not even talking to friends or family about how they’re struggling. They’re not talking in any way, shape, or form to anyone. This service is just incredibly important. It’s totally needed. Our service, in a moment of crisis, helps people connect in a nonjudgmental way, and we need more communities and more people with those skills.

Catherine Edwards: How do you see your work evolving over the next five years?

Dena Trujillo: We’re really going to double down on expanding volunteering now that we have this research data. We’re going to be spreading our volunteer community so that more and more people can feel that sense of agency, and we can build up the workforce. About 30% of our volunteers say that their career choices relate directly to volunteering. We are also going to be sharing our technology with organizations around the world, so that more people can have the data and the platforms to be able to lift up ships, and do the same work in their local countries.

Expanding volunteering. Spreading the technology and research so more people can use it. And focusing on more partnerships, working with governments, working with nonprofits, and working with corporations.

Catherine Edwards: Is there anything you think is important to mention that I haven’t asked about today? Is there anything else that you want to add or emphasize?

Dena Trujillo: One thing I forgot to mention is that, in the US, we offer our service in Spanish. Only a very small percent of mental health partners do this in Spanish, but because of those needs, we’ve added Spanish. I would also say that everyone is impacted by mental health, but our communities that are the most marginalized, especially our people of color and our LGBTQ communities, often have the higher levels of trauma. That is what Black boys 13 and younger are twice as likely to end their life by suicide than white boys of the same age. That’s just one example of many examples I can give.

We have to focus on everyone, but our work and mental health equity of people of color upfront do that. That’s all part of what I’m really looking forward to in the next five years. Digging deeper into helping identify where there are gaps in mental health provision and services and to face it so we can do a better job of identifying areas of inequity in mental health provision and services, and help to close those gaps.

Catherine Edwards: Thank you so much for your insight, it will be really helpful to people.

Click here to read the full conversation with insights highlighted.

Catherine Edwards is a journalist and content strategist based in the UK, having also lived and worked in Germany, Italy, Sweden and Austria. She supports newsrooms and mission-driven organisations with content strategy, audience development and constructive journalism.

* This interview has been edited and condensed.

Learn about other organizations working on innovations in mental health support.